The first time Gregg Garfield even heard of the coronavirus was in late February, when his fiancée, Anneliese “AJ” Johnson, called him on his European ski trip to warn him there had been an outbreak of COVID-19, the illness the virus causes, in Northern Italy.

“That’s where I am!” responded the surprised 54-year-old, an avid amateur skier who has enjoyed as many as 100 days a year on the slopes. Gregg has always been a risk taker who loves the adrenaline rush of high-octane sports including car racing and motorcycle riding. He’d even survived an avalanche while skiing a few years back. “He has always lived each day like it was his last,” says AJ fondly.

But in this case, Gregg didn’t think he was facing much risk. “I didn’t know much about the virus at the time and quite frankly, I wasn’t really worried,” he recalls. After AJ’s call, Gregg, along with a dozen of his buddies, returned to skiing the Dolomites in Val Gardena.

Little did Gregg know that, shortly after that call, his life would be flipped upside down. He was about to take on a new identity: COVID Patient Zero, as he was dubbed upon admission to Providence St. Joseph Medical Center.

Superspreader Event

Gregg thinks he contracted the virus the very first day in Val Gardena on the tightly packed gondola that ferried his group to the top of the run, although the identity of the superspreader has never been determined. Each day, 50 eager skiers would fight their way aboard the overcrowded gondola. “It was a mosh pit,” recalls Gregg. “It was actual rugby.”

Out of his 12 ski trip companions, all got COVID, although none were as critically ill as Gregg, who spent a total of 64 days at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, 31 of them on a ventilator, sedated and paralyzed. He remembers nothing of the month he spent in isolation, during which time his kidneys failed, his lungs collapsed repeatedly, and he developed a pulmonary embolism, blood clots, and sepsis. At one point, his fever spiked to 103.6 and he was packed in ice.

As he was being prepped for intubation, he recalls, “I was really scared. I said to the nurse, ‘I don’t want to die.’ She said, ‘I promise I won’t let you die.’ Later, she told me, ‘I was afraid I had made a promise to you that I couldn’t keep.’”

Although surviving a month on a ventilator was the most challenging hurdle, Gregg’s ordeal is far from over. He is facing a $2.5 million medical bill that will ultimately swell to $3 million. Gregg’s health insurance is covering his hospitalization, but related care and rehabilitation expenses, such as any prostheses, are not part of the coverage.

He has lost all of the fingers on his dominant right hand and the first two joints of the fingers on his left hand as well as three toes due to complications from COVID. He is facing at least five more surgeries over the next eight months to restore enough function to his hands so he can wear a prosthesis.

Gregg and AJ want to spread the word that COVID isn’t just a flu with attitude or a really, really bad cold. And that it can make robustly healthy, low-risk people very sick. Or even kill them, as it nearly did Gregg, who cheated death day after day. They want people to understand that taking precautions to avoid spreading the virus isn’t a political issue; it’s common sense. “If there’s one message we can send,” says AJ, “it’s that people need to be safe and responsible.”

“We really want to be advocates of getting ahead of the virus and understanding the severity of it,” adds Gregg. One of his most visible appearances, a May 29 interview with Ellen DeGeneres on ellentube, garnered 1,800 comments, and it’s clear from most of them that his message has been heard: “COVID is a NASTY thing,” wrote one typical viewer.

ABOVE: Gregg with his friends on February 26, a week before he got sick

A Turn for the Worse

As with many people who become deathly ill with COVID, Gregg’s symptoms were relatively mild in the first week to 10 days. He skipped three days of skiing because he thought he had the flu, but finished out his trip. After learning of one companion’s positive COVID test while on his return flight to LAX on March 1, Gregg self-quarantined at his comfortable California ranch-style home with his Newfoundland-Labrador mix, Bear, as company.

“I wanted to get a COVID test, but they just weren’t readily available like they are now,” Gregg explains. He contacted his former general practitioner for help. The GP in turn alerted the Centers for Disease Control office in Pacoima. On March 2, officials there dispatched a van with hazmat-suited personnel who brought Garfield to their field office, where he tested positive.

Then suddenly on March 4, nine days after his presumed exposure and still quarantined at home, “Everything went sideways. I was talking to a buddy on the phone and he said, ‘Dude, you’re not good.’” Although he didn’t realize it at the time, Gregg was confused and listless; his friend immediately contacted a mutual friend who is a doctor.

While the doctor called around to large medical facilities in LA looking for one that was ready and willing to admit a COVID patient, Gregg was on the phone frantically seeking someone who would take care of Bear. He even called the fire and police departments, but no one was prepared to enter a home where there was an active COVID infection. He ended up leaving his beloved dog crated. “It was this moment of desperation. Here I find out I’m really sick, but my thoughts are all on my dog. I was completely distraught thinking about leaving her in that crate,” he recalls. Gregg went by ambulance to Providence St. Joseph’s at 4 a.m. on March 5.

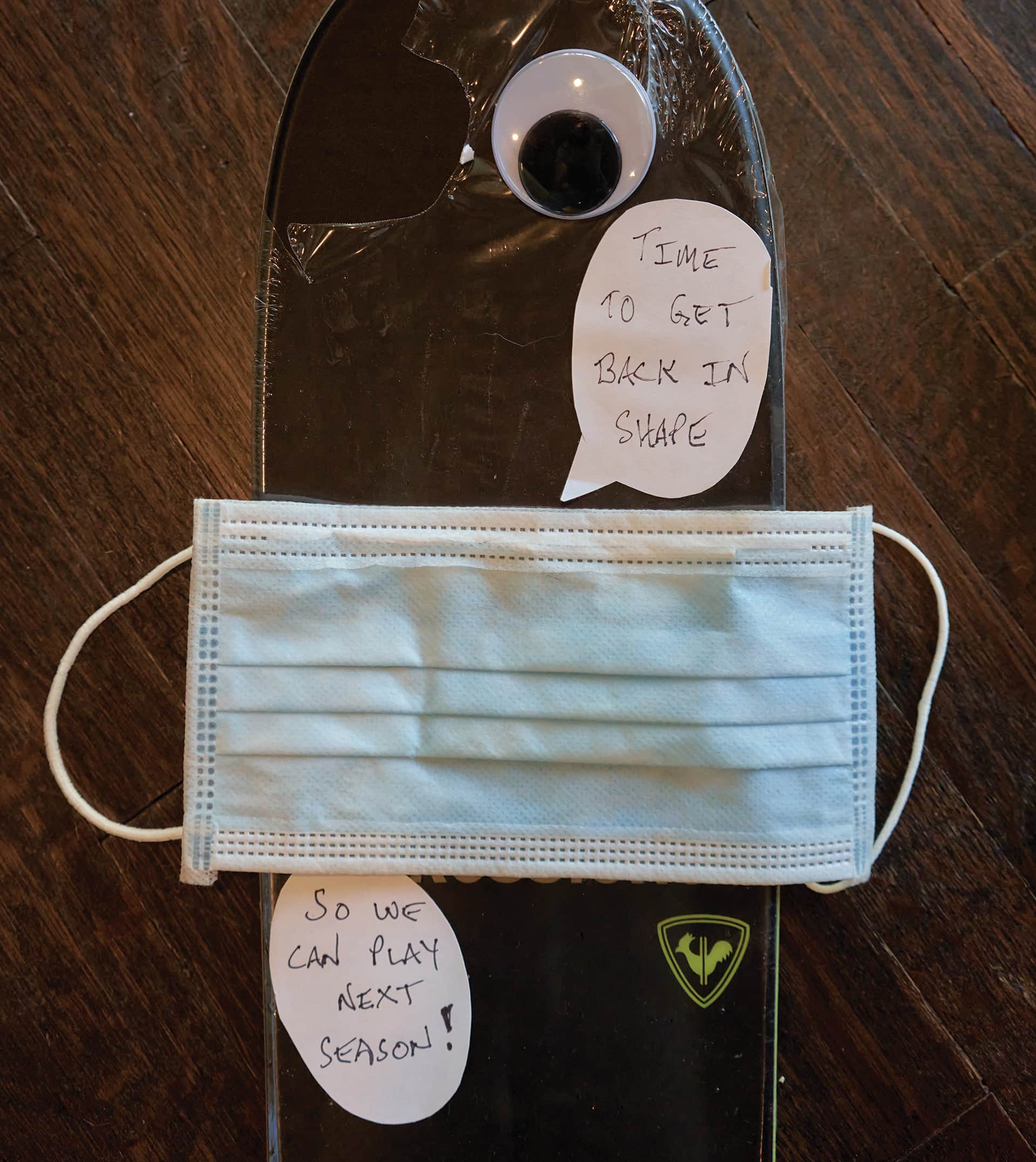

A pair of skis that a friend gave him as a gift.

Hospital Drama

Gregg would be the medical center’s only COVID patient for a full week. Daniel K. Dea, MD, a pulmonologist and critical-care specialist who became the leader of Gregg’s care team for the next two months, remembers first meeting Gregg that day and says, “He was very frightened. This is a guy who almost died.”

Dr. Dea himself was encountering COVID for the first time, although colleagues at a Providence hospital in Washington State, where the West Coast’s first case had occurred on January 21, had been helping the Burbank team prepare. “We were ready,” recalls Dr. Dea. “We had the best doctors and most experienced nurses ready, and we poured resources into Gregg.” While “it’s not a surprise now,” says Dr. Dea, it was initially shocking to medical professionals “how quickly a COVID patient can go bad.”

AJ, meanwhile, was being trained by one of the Providence St. Joseph critical-care nurses on how to safely enter a COVID-infected residence so she could rescue Bear, the dog, who was still stuck in her crate in Valley Village. Dressed in full protective gear, and moving as quickly as she could, AJ let herself into the house around 8 p.m., washed Bear on the deck with a special antiviral shampoo, and then stripped down. “I was literally buck naked in the yard! Honestly, with all the clunky gear on—every inch of me covered—and my heart beating like mad, it was like something in a sci-fi movie!” she says.

Two days later, things took an even more frightening turn. On March 7, Gregg’s oxygen levels dropped dangerously low. To keep him alive, doctors heavily sedated and intubated him. He recalls talking on the phone to his girlfriend just before the procedure: “I said to AJ, ‘I’m going to be offline for a couple days.’” As it turned out, two days was optimistic.

Gregg’s Village

With Gregg intubated, AJ, a wealth manager with two kids of her own, and Gregg’s sister, Stephanie Garfield Bruno, took over the task of communicating with his circle of friends and growing audience of well-wishers. Stephanie had rushed to Los Angeles from her home in Silicon Valley and would spend three weeks living at AJ’s place in Woodland Hills as they struggled to manage Gregg’s care remotely and keep his credit-card-processing business and finances afloat. “AJ was the quarterback of it all,” notes Gregg.

Working together, the two women crafted three text messages a day that went to an initial list of 40 friends, eventually spreading to people worldwide as the texts were shared and shared again. Although they gave recipients a realistic idea of what was happening, Stephanie and AJ always included at least one positive element in the reports, no matter how bleak the picture was at the time. “We tried to keep the energy high,” says AJ. “This whole experience showed how important keeping the vibration positive is.”

The collected texts serve as a cliff-hanger diary of a near-death experience, and AJ wasn’t sure Gregg would want to read them. “When I got out of the hospital, AJ asked if I was strong enough to go through all the text messages.” He did read them: “I wanted to experience what they went through,” he says, and to learn what had happened to him day by day.

The experience has left Gregg with unlimited gratitude to the 186 health professionals who helped him and the thousands of people around the world who followed the daily briefings and expressed love and support. Stephanie set up a GoFundMe account to help pay for Gregg’s recovery; to date it has raised more than $207,000 from 1,200 donors, most of them giving in the $5 to $50 range. The GoFundMe page that tells Gregg’s story has been shared 5,500 times.

“The team that took care of me are the heroes,” Gregg says. “I’m the luckiest person alive.” As a special thank-you, he has asked a friend to make pewter-colored scrubs emblazoned with “Gregg’s Village” for all the doctors, nurses, and techs who played a role in his care.

As an indication of how widely Gregg’s supporters were dispersed, the text diary eventually connected AJ with Amanda Kloots, wife of Broadway and TV actor Nick Cordero, who was also battling COVID. The 41-year-old Cordero was sick for 95 days, with his wife offering her own daily updates via Instagram. The actor lost a leg due to a blood clot during his hospitalization at Cedars-Sinai, and ultimately died on June 5 .

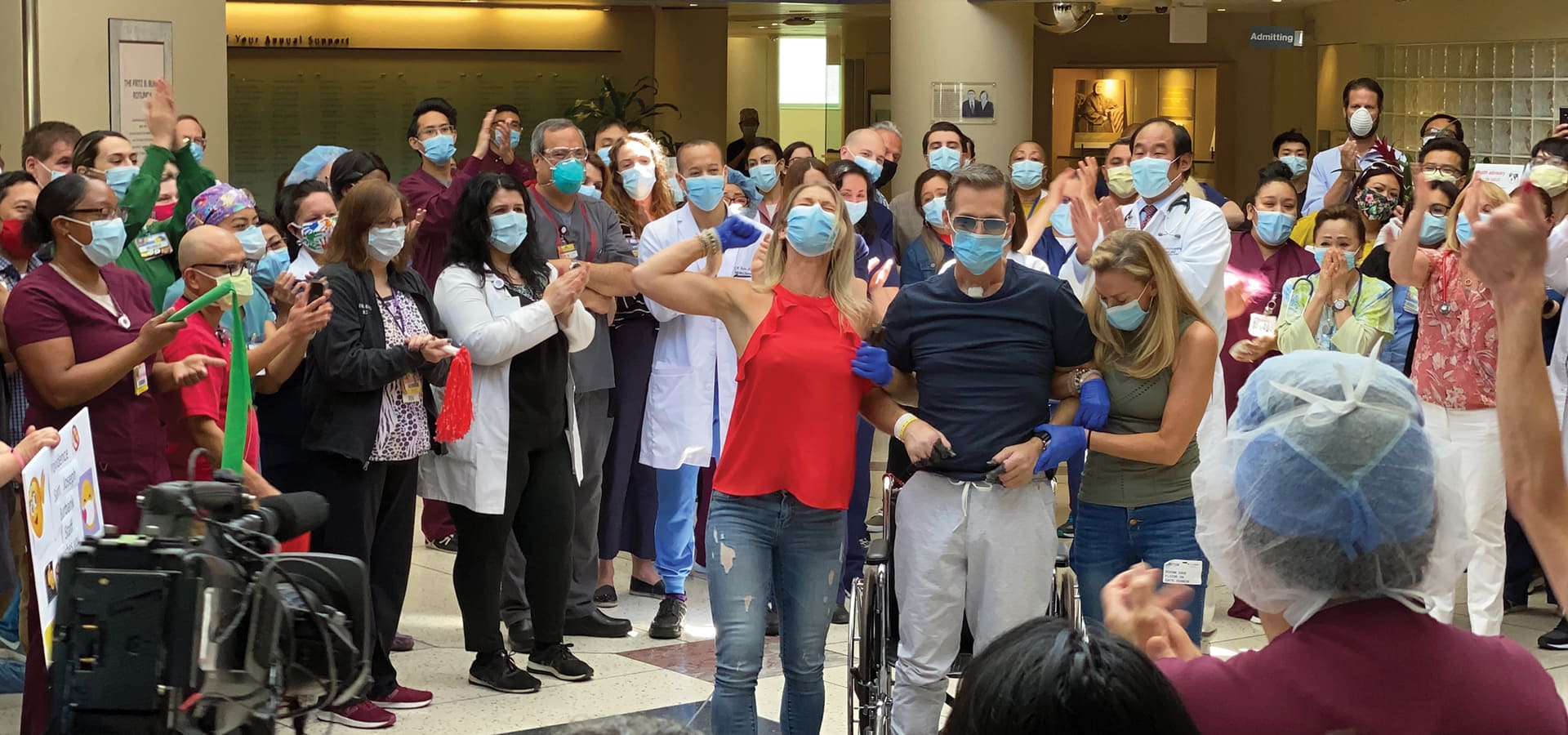

ABOVE: The hospital staff cheering on his May 8 release

Turning the Corner

One of medicine’s most persistent mysteries is why one person survives and another dies. Treatments that save one person may not work for another. In Gregg’s case, it seems like the antiviral remdesivir was a deciding factor in his recovery. Dr. Dea also credits the patient himself: “He was very strong as an athlete,” he notes, “and mentally he was very tough.”

At the time of Gregg’s hospitalization, medical researchers were just beginning to observe improvement in some severely ill COVID patients given remdesivir. Starting in January, Gilead Sciences, the maker of the drug, had been providing it to critically ill patients on a limited basis under a protocol known as “compassionate use.” In Gregg’s case, the day he completed the 10-day course of treatment in mid-March, he turned a corner. On March 19, he tested negative for COVID for the first time. He would need another month in the hospital, but good news was on the horizon: He was going to live.

Once off the ventilator, Gregg made the slow return to consciousness. “For me, days 31 to 64 were the start of my journey,” he says. While sedated, paralyzed, and dependent on the ventilator to breathe, Gregg had lost 50 pounds and his fingers and three toes had turned black from the death of tissue. On day 31, he began the process of learning to walk again, as well as to speak and to chew and swallow. Entering the second month of his hospitalization, he became an active participant in his recovery.

At Providence St. Joseph’s on March 27, before Gregg was intubated.

A Life Changed

Since leaving the hospital, Gregg has been under the care of David Kulber, MD, a Cedars-Sinai hand surgeon. The doctor has been performing a series of delicate and complex surgeries on Gregg, preparing him for what the patient describes as “the Ferrari of prosthetics,” an elegant mechanical hand that costs $100,000.

Although Gregg’s finger loss is unusual in COVID patients, it is not unique. Dr. Kulber says that he has seen four or five other patients recently who experienced the same problem—inflammatory damage caused by the coronavirus infection to the tiny blood vessels that perfuse the fingers and toes. Starved of oxygen, the appendages gradually die, just as they would from frostbite.

In Gregg’s case, the situation may have been worsened by the administration of Levophed, an IV drug given to increase blood pressure when it drops disastrously low. Levophed, a vasopressor, works by constricting blood flow to the extremities, meaning it can compromise circulation in the hands and feet even in non-COVID patients.

Dr. Kulber says he has been impressed both with Gregg’s attitude and with his desire to spread the word about the dangers of COVID. “Gregg’s one of those people who asks what he needs to do to move on. He’s a survivor,” says Dr. Kulber. “He’s really gone on the offensive to tell people about COVID. It’s nice to see someone with a positive attitude who wants to help other people.”

So far, Dr. Kulber has “cleaned up” Gregg’s fingers and thumbs. “We never said ‘amputation,’” the physician explains. “It was clear to me that wasn’t something Gregg wanted to hear.” He has also started to build up the remaining healthy tissue so that the right hand can accommodate a prosthesis and the left hand, which still has finger stubs, will be more functional. He may end up putting in bone extenders—a mechanical device that lengthens the remaining bone millimeter by millimeter—but he isn’t sure yet whether it will be necessary.

In spite of the daunting medical procedures and long rehabilitation ahead, Gregg glances over his shoulder and smiles at a still-shrink-wrapped gift from a friend: new Rossignol skis. Without a hint of reserve, he says, “I will definitely be skiing again. It will be a huge event. COVID was a life-changing experience, but it’s not going to change my life.”

Join the Valley Community