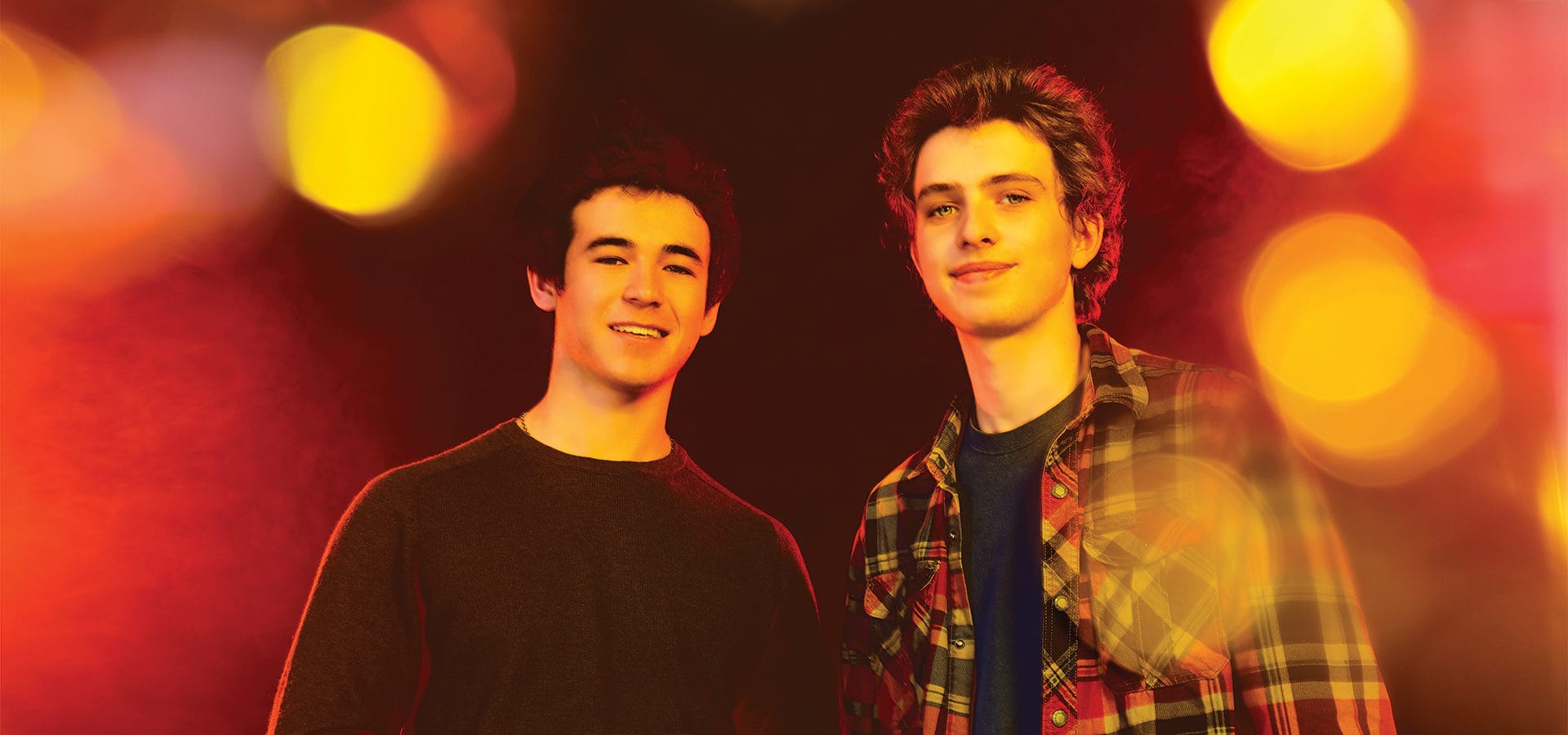

Teenagers Jack Barrett and Mason Lee Join The California Conservation Corps to Fight Wildfires

On the front lines.

-

CategoryPeople

-

Written byLinda Grasso

-

Photographed byMichael Becker

When Jack Barrett and Mason Lee graduated from The Buckley School in the spring of 2020, they had big plans for college. Both had excelled academically. Jack had been accepted at Reed College; Mason was headed for Brown University. Then COVID hit. But rethinking the decision to attend college was about more than the pandemic.

“It wasn’t that I wanted a break from education. I wanted to experience education in a different way,” explains Jack.

Mason, on the other hand, did want an academic respite. Perhaps even more so, though, he wanted to do something related to helping the environment. Mason conducted research throughout high school focused on healing the environment through technology. He also won the LA Science Fair and got his first paper—on using bacteria to degrade industrial pollutants in marine ecosystems—published in the Journal of Emerging Investigators. Currently he is working on new research that aims to remediate pollutants on land scarred by burned houses using oyster mushrooms.

“We were on the most active part of the fire and had to stop the spread before it ran through the canyons. We started cutting line. About an hour into it, a flaming branch shattered on my head, knocking me down. It was a scary moment.”

“I aim to holistically heal the environment with noninvasive remediation techniques that build upon the native knowledge of the land,” he says.

With their college acceptances hanging in the balance, Mason came up with an idea. What about signing up with the California Conservation Corps for a year? The CCC provides young adults ages 18 to 25 a year of paid service to the state. Corps members work on environmental projects such as planting trees, building backcountry trails and improving fish habitat. They also respond to natural disasters, from fires to earthquakes. With the motto “Hard Work, Low Pay, Miserable Conditions and More!” the program aims to give young people skills and experience that lead to meaningful careers.

“Jack is like my second brother. We share that adventurous spirit and he’s always willing to put himself out there. We are kind of opposites in many ways as well. In terms of academic interests and political views we definitely argue a lot,” notes Mason.

“Jack is like my second brother. We share that adventurous spirit and he’s always willing to put himself out there. We are kind of opposites in many ways as well. In terms of academic interests and political views we definitely argue a lot,” notes Mason.

There was no debate, however, on the CCC. Jack and Mason applied, were accepted, and arrived at the residential center—base camp—in Placer County, north of Sacramento, in early July. They almost immediately started two weeks of basic job training and two weeks of basic fire training. The latter involved a grueling physical test.

“You had to complete a 2-mile run in less than 18 minutes, do 25 push-ups, 25 sit-ups, five pull-ups, and—the most challenging part—a 1-mile hike at 20% grade. During the hike you have to carry 30 pounds and a tool—while wearing full head-to-toe fire gear. All in 100-degree-plus heat,” recalls Jack, a physically fit, avid rock climber, who admits he threw up during the test.

After they finished basic fire training, they left base camp for their first assignment, the Gold Fire in Lassen County. The teens quickly learned that fighting a raging wildfire was less about their training and more about learning on the job from California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) teams as well as experienced CCC members. Those corps members “come from all walks of life,” says Jack. They include women, professionals who are seeking something different, and young people who have come through the state’s juvenile justice system.

Mason at the August Complex Fire.

“As the new guy on the crew, you shut up and watch and learn from the others. You make mistakes, but that’s expected. You need to put your head down and work and you catch on fast,” says Mason.

After the Gold Fire, the teens crisscrossed Northern California, working the Jones Fire in Yuba City, the Sheep Fire in Susanville, the Willow Fire in Placer County and finally the August Complex Fire in Humboldt County. That last wildfire, which was caused by lightning, raged over more than a million acres, killing one firefighter and injuring two.

Mason remembers the day they arrived at the site. The squad had driven five hours from base camp to get to the fire line.

“We rolled over a mountain ridge and saw several huge smoke columns blocking out the sun. It was intimidating. We drove in and the forest began to get smokier and smokier. Eventually we reached our drop point, convened with regional commanders and got the briefing. We were on the most active part of the fire and had to stop the spread before it ran through the canyons. We started cutting line. About an hour into it, a flaming branch shattered on my head, knocking me down. It was a scary moment.”

Minutes later, firefighters in heavy-lifting Chinook helicopters started dropping water. “They were blind dropping. You couldn’t see the tops of the trees because of the fire. I looked up and saw a waterfall coming down. I took two steps and jumped to the ground. It felt like I got hit by a car,” Mason recalls.

For 18 hours, the squad maneuvered the steep canyons, cutting line. When fire burned over their line, they were forced to evacuate.

For Jack, the most harrowing moment came during the Jones Fire. They were called out at 3:30 a.m. and didn’t have time to pack food.

“That was my first time getting that close to wildfire, so it was pretty exhilarating. However, on empty stomachs and lacking water, many members on my crew including myself started to exhibit symptoms of heat exhaustion. So we had to retreat maybe six or seven hours into our line cut.”

With the worst wildfire season in state history, Mason and Jack’s assignments were pretty much back-to-back from July to October.

“We were the first and one of the only resources on several fires. Having four crews on the initial attack phase of a 32,000-acre fire was unheard of before this year, but it was a reality we had to deal with. We were more exposed at times when there were not enough engine resources to lay hoses for us. We had to work longer and harder, cover more ground, and wait longer for relief crews to come. We rarely saw other fire crews on the line,” says Mason.

They’d work in 24-hour shifts and then get a day off. The grueling schedule began to take its toll.

“Your body shuts down physically and mentally, increasingly, with each shift. Sleep deprivation is unavoidable and it really messes up your cognition,“ says Mason.

A selfie that Jack sent to friends.

“In that time frame you might get four to eight hours of sleep (in shifts) if the fire is mostly out and in mop-up phase. But if the fire is at low containment, that means getting from zero to four hours of sleep,” says Jack.

Ask Jack whether he got more than he bargained for in signing up for the CCC and you’ll get a quick no. “Hand line crews have been doing this kind of work and getting their asses kicked for years. Looking into the program online, I sort of expected this kind of experience. I feel lucky that I got to work and be helpful this year.”

Mason says one of the most valuable things he’s gained from the experience is perspective. “Perspective allows you to look beyond your paradigms to see the struggle of others. You can understand someone’s struggle on the surface, but you can’t internalize it until you are right there walking in their boots,” Mason says.

As for Jack’s most important takeaway, “Somebody told me at the start of my fire training that I had to get comfortable being uncomfortable to succeed not just in firefighting, but life. I think that is some of the best advice I have ever received.”

Jack says he highly encourages other high school students to consider the CCC for a gap year.

“The experience will provide a level of perspective and insight that is more educational than a year of college, especially during COVID. It also can lead to a career with CAL FIRE if you apply yourself. You can get a seasonal job that pays $80,000 a year, with a pretty awesome work schedule—half a year of firefighting, half a year of travel.”

Both Jack and Mason are back at CCC base camp finishing out their year of service and making plans for the future. Reed College would not allow Jack to defer, requiring him to reapply. However, he has decided to go in a different direction.

“I like Reed, but I think it fits my personal philosophy a bit too much. I think I would feel more challenged and engaged at a larger school that caters to a different ethos than my own,” Jack shares.

Brown University, on the other hand, permitted Mason to take a gap year, and he’ll attend the school in the fall. He intends to study mycology and environmental engineering. He says he will take what he has learned with the CCC with him.

“Work hard. Have integrity in your life. And take extreme responsibility for it. There are people fighting for every bit that they have. You can’t look at that and take things for granted in your life.”