Rock of Ages

Rocks carved by the millennia anchor the northwest corner of the San Fernando Valley.

A visit to Stoney Point Park reveals 10 views of a suburban legend.

-

CategoryUncategorized

ONE

Seventy-five million years ago, Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument 132 began its epochal eruption as a cloudy slurry of feldspar, quartz and granitic rock particles drifting 1,000 feet to the ocean floor. On land, dinosaurs flourished. In the water, marine reptiles and sharks plumbed the depths. Fossils of mollusks found in the rock date it to the Late Cretaceous period.

According to Marilyn Tennyson, a research geologist for the U.S. Geological Survey, Stoney Point is likely to be some combination of locally harder or coarser sandstone that resisted erosion better than the surrounding rock. Today, the rocks tagged with spray paint are clearly in the age of urban blight.

TWO

In his book Urban Rock: Stoney Point Bouldering & Top Roping, Chris Owen graphed this city park like a cartographer charting 1,000 routes to the Promised Land. What to the untrained eye is a natural wonder with flat surfaces of sun-parched stone becomes, on the page, a complex skein of measured, analyzed and interpreted geology.

The anonymous rock claimed and identified Crown of Thorns, Mozart’s Wall, Pin Scars, Tower of Pain, Turlock, Ummagumma and Yabo Mantle. The route descriptions ring with the poetic lilt of the exotic: “Left side pull, right sloper; a knee bar enables shorties to grab small crimp. Good holds on the arete to iffy top out.”

THREE

For 80 years, some of the sport’s most respected and revered climbers have puzzled out rock problems at Stoney Point. In the 1930s, Sierra Club climber Glen Dawson trained here before putting up first ascents in the High Sierras. In the 1950s, Royal Robbins and Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard hopped Southern Pacific freight trains to The Point to hone their craft and develop techniques, like clean climbing, that would guide the sport toward a low-impact approach.

The next 30 years heralded the arrival of free climbing, with its focus on minimal aid, and free soloing—climbing hundreds if not thousands of feet up a rock face without rope. And all those practitioners spent time at Stoney Point.

“This dusty pile of rocks on the side of the road has been very influential on some of America’s legendary climbers,” says Cole Gibson, director and co-producer with Matthew Talesfore of the documentary, Stoney Point: Portrait of an American Crag. “These guys went on to affect the culture of climbing throughout the world.”

FOUR

Stoney Point has the hide of a vagrant—the scarred, pockmarked surface of the abused but unbowed. Much is made of the glass and the graffiti—the incessant urban encroachment on an historical landmark. But these are cosmetic injustices.

Get close to the rock, and you will understand and know its real beauty, feel its varied and rich history. Start climbing here, and you will become part of a community that takes the rock’s measure day after day and discovers what it means to be part of something larger than itself.

The diehard climbers are just as resolute as the rock, and they are the true stewards of Stoney Point, not the city officials taxed with its upkeep. Most major clean-up efforts are organized by climbers or groups like REI and the Boy Scouts. Without these outside efforts, Stoney Point may have long ago fallen to the tweakers, taggers and drunks.

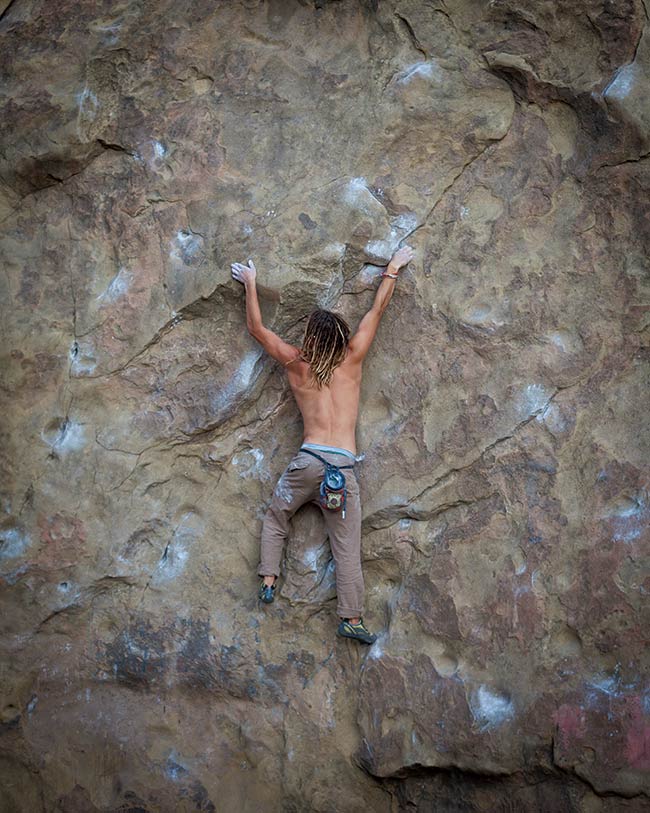

Jason Ambrose ready to ascend Boulder 1.

FIVE

The luminous white scuffs of chalk mark The Point’s sandstone and hint at the trials and tendon-stretching ululations of a climber’s journey to the top. Even for the uninitiated, these glowing tracks speak of a primitive desire.

Says Chris Owen, “People in Los Angeles are so wrapped up in city life that this offers an important outlet for the visceral self in all of us.” For more than 30 years, some of the same climbers have hauled their crash pads and chalk bags to The Point every Tuesday and Thursday to wrestle with climbing conundrums.

Guy Keesee and Mark Frumkin started going in the 1970s; Chris Owen touched rock there for the first time the 1980s, and Brad Bell began his weekly pilgrimage in 1990. This group of regulars welcomes anyone interested in testing their mettle on the rock.

SIX

On a warm October evening a few weeks before Halloween, a group of shirtless men equipped with headlamps worry at the face of Jam Rock; they are attempting to pull themselves through a bouldering route called Aftershock. The mood is jubilant. Each man lunges at the thin spit of sandstone above his head, but none can grip it for long.Then Andrew Rock (yes, that’s his real name) approaches the poorly lit boulder and without hesitation heaves up for the hold. A Stoney Point regular since fifth grade, Rock, now 37, is known at the crag for his methodical and almost flawless execution. And on this day, he doesn’t disappoint.

Clinging by what appears to be his fingernails, he stalls ever so slightly, then finds a grip with his free hand and pulls himself effortlessly through the route. Collective envy leavened with awe and good cheer washes through the night.

Chris Owen, a regular here for some 28 years, traverses rock.

SEVEN

From the topmost rock of Stoney Point, the San Fernando Valley stretches, scored and glittering like an urban prairie of subdivisions and industrial parks, until it’s lost in a soup of mocha haze. Mountain ranges push at the landscape in every direction.

Beyond Topanga Canyon Boulevard, heading northwest, the Santa Susana Pass meanders through the Simi Hills, where more than 2,000 Hollywood movies and television shows were filmed on the Iverson Ranch, including John Wayne’s The Fighting Seebees and Bonanza, Gunsmoke and The Virginian. In that same hemorrhage of rock, on the neighboring Spahn Ranch, the Manson family made their home and plotted their heinous crimes against humanity.

EIGHT

The horror of a big fall is a rare event at The Point. Death and dismemberment take distant second to the small devastations of broken ankles, heels and wrists. Blown finger tendons reign as a nasty debilitation that can keep a climber off the rock for a year.

Owen, who has climbed at Stoney Point since 1984, admits to having carried his fair share of climbers out to the street for medical attention. But the big losses for Stoney Point have happened elsewhere: the elite climbers who cut their teeth for years on Boulder 1 and Turlock, ventured out into the world where they were equally comfortable, and never returned.

John Bacher, killed free soloing near his home in Mammoth Lakes. Michael Reardon, swept off a cliff by a rogue wave after completing a climb on the coast of Ireland. John Yablonski, a legend here, who has several climbs named after him, taking his own life—a fearless climber with a head full of demons. Climbing comes with inherent risk but need be not performed near the redline to be a rewarding and exhilarating challenge.

NINE

Free, accessible and loaded with enough problems to keep a climber challenged and progressing for years, Stoney Point is still considered a training ground for bigger, more ambitious climbs. The Tuesday/Thursday group exists as the necessary result of weekends in Joshua Tree, or on Tahquitz near Idyllwild, or in Toulumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park.

As Mark Frumkin, a 30-year Stoney Point veteran points out, “Mondays are for recovering from the weekend and Fridays are for getting your gear ready to go again.” But some climbers find that The Point offers everything they need.

Brad Bell has climbed other rock, but for more than 20 years, he says, he has mostly just climbed at Stoney Point. “There are a lot of problems to work out. Besides, the camaraderie and the friendly people make it a great place to be.”

TEN

Stoney Point resonates beyond its humble pile-up in a scorched corner of The Valley. Boulder 1, the main boulder in the open plain as you come off the embankment from Topanga Canyon Boulevard, has been called America’s most traveled piece of rock.

Weekends at The Point are thronged with climbers, both bouldering and top roping. The sandstone is known for its softness, which makes it both easy to climb on for long periods of time and vulnerable to breaking. “The rock quality may not be world-class,” says Cole Gibson, “but this is basically LA’s free outdoor climbing gym.”

But climbing is only part of the Stoney Point legend. According to Mark Frumkin, he has seen it all over the past 30 years. Fist fight, pornography, music videos. In the ‘70s, he says, there would be a new band showing up every weekend.

“One day these guys got out of a van and said, ‘We just got here from Alabama.’ And I remember thinking, ‘You passed the Grand Canyon for this?’” Indeed. In more ways than one, Stoney Point is resistant to corrosion.