Holding Out Hope

Former home to a well-known entertainer that can be sold and subdivided? Or historic LA landmark that should be preserved? The family of Bob Hope can’t sell the sprawling Toluca Lake estate—until the city decides.

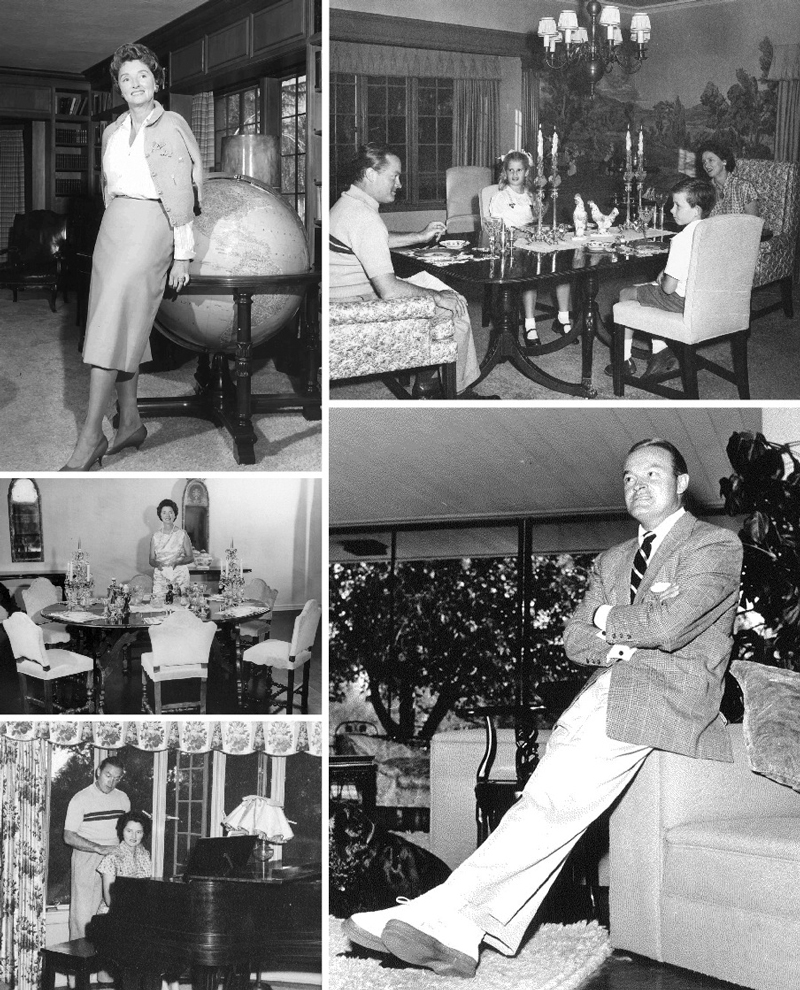

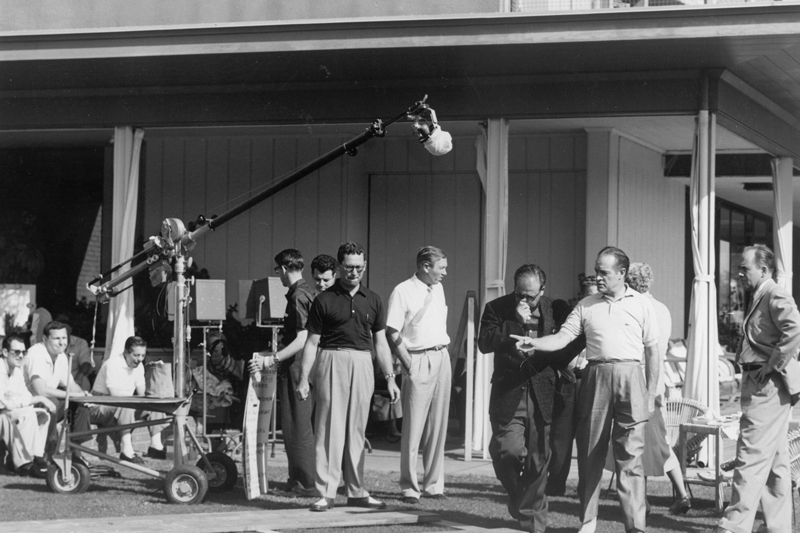

PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF THE BOB HOPE LEGACY

Bob Hope may have gotten four stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. But from 1939 to his death at age 100 in 2003, the entertainer’s favorite place in Los Angeles was on the other side of the hill—at 10346 Moorpark Street in Toluca Lake.

Hidden from the street behind fences and dense privacy hedges, passersby would never guess that the Bob and Dolores Hope estate occupies 5.16 acres with a two-story main house of almost 15,000 square feet. Other structures on the expansive property include a two-bedroom guesthouse with staff quarters, a swimming pool, rose garden and one-hole putting green.

Although the couple owned a second home—a distinctive mushroom-shaped Palm Springs residence designed by Modernist architect John Lautner—daughter Linda Hope has called the Toluca Lake residence that her parents shared for more than 60 years the couple’s “dream house.” (The Palm Springs home, built in 1980, has also been for sale since 2013.)

While you can’t see the home from the street, the Toluca Lake community is well aware that Bob Hope slept here. Says journalist Susan King, creator of the Los Angeles Times’ Classic Hollywood column and a 24-year Toluca Lake resident, “I still love to pass the Hope mansion because it’s truly from an era long gone.”

During her years covering entertainment, Susan visited the Hope estate. “I had lunch with Hope at his house in 1991 for Christmas. He always had lunch with reporters in a family room that looked like it had been decorated from the Vermont Country Store catalog,” Susan recalls. “But what really stood out in that room was the bay window where the table was located. I felt like I really stepped into old Hollywood looking out that window during the interview and seeing that expansive acreage perfectly manicured, that just seemed to go on forever.”

Dolores Hope died in 2011 (at the age of 102), and the estate is now owned by the Bob & Dolores Hope Foundation, a nonprofit with the mission to help the needy as well as to support U.S. military personnel.

As the house remains hidden from view, the Hope estate has recently been thrust into the spotlight by a debate over whether the property should be designated a historic and cultural monument because of its prominent owner.

The Toluca Lake estate was originally put up for sale for $25 million. Two years later, in 2015, the price was dropped to $23 million. Then this past summer the listing suddenly and dramatically changed. The new listing, repped by realtor Craig Strong with the John Aaroe Group, offered only part of the property—the main house and some of the land—for $12 million. The insinuation was clear; the rest of the property would ultimately be available to a buyer, possibly for development.

In September, the city got involved. City councilmember David Ryu, whose district includes Toluca Lake, moved to have the property considered for preservation as a historic and cultural monument. Ryu took action after Linda Hope filed for demolition permits for some structures on the property. Turns out Dolores Hope’s will included a title restriction that prevented a buyer from subdividing the property for five years after her death; the clause expired in 2016, allowing Linda Hope to request permits for a potential buyer. Once demolition permits are given, the city loses its option to halt demolition. Ryu’s motion was unanimously passed by the City Council.

The next step: The Cultural Heritage Commission, part of the city’s planning department, will make its recommendation. While the property can still be sold, a historic designation may complicate the sale by limiting the buyer’s options on what that buyer may do with the property. And if the designation thwarts a sale, maintenance costs—an estimated million dollars a year—will continue to cut into the Hope Foundation’s resources.

Craig Strong declined comment—saying he wanted to wait until the situation was resolved. But he was quoted in The Hollywood Reporter saying a probable sale by a qualified buyer “went south” after the emergency legislation. Strong said the buyer planned to restore the main home and was only considering tearing down a detached office space and a garage. “The closing was just two weeks away and the city didn’t ask what was going on—they just acted,” Strong said in the article.

Linda Hope also declined our request to be interviewed. Her spokesperson says she has been asked by city officials to refrain from speaking to the press until after an inspection of the property.

Through that same spokesperson, the Hope family issued a statement saying Linda had been “surprised” upon a return from travels to find a whirlwind of “misinformation” swirling in the press about the estate.

The statement reads in part: “The Hope family and The Bob and Dolores Hope Foundation have been diligently making every effort to make the final wishes of both Bob and Dolores a reality. First and foremost in this attempt, is that the money raised by the sale of the estate will be a source of ongoing support to those organizations that bring “Hope” to those in need and those who served to protect our nation … ”

In the meantime, some are wondering if the property meets the criteria for a historic designation. As the estate was being put on the market, a 2013 Los Angeles Historic Resources Survey listed it as “potentially historic.” The main structure was designed by architect Robert Finkelhor and extensively updated and expanded in the 1950s by architect John Elgin Woolf. Woolf was an architect to the stars; clients included Cary Grant, Judy Garland and Katharine Hepburn.

Ken Bernstein, principal city planner and manager for the city’s Office of Historic Resources, says that with so many celebrity residences in Los Angeles, there is a “fairly high bar” for designation. “It’s the Los Angeles equivalent of the ‘George Washington slept here’ syndrome back East,” he jokes.

“I still love to pass the Hope mansion because it’s truly from an era long gone.”

First, no B-list stars, according to Bernstein. Second, a house must be associated with a “productive period” of the celebrity’s career. And finally, the home’s architectural significance plays a role.

For example, a year or two ago a Marilyn Monroe residence in Valley Village came under consideration. But she only lived there for about a year, Bernstein said. Plus she lived in Valley Village in the early days when she was still an unknown named Norma Jean. Certainly Bob and Dolores Hope far exceed the bar in terms of spending their productive years in the Toluca Lake home.

Earlier this year, Burbank’s Bob Hope Airport was officially renamed Hollywood Burbank Airport to increase geographical recognition with passengers outside of Southern California. But locals will most likely associate the Toluca Lake estate with Hope forever, no matter who lives there.

POSH PAD The Hopes moved to the estate in 1939,and it’s been added

POSH PAD The Hopes moved to the estate in 1939,and it’s been added

onto and expanded many times over the years.

Stories abound about drop-ins from neighbors Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra. Those who grew up in the neighborhood remember awesome Halloween loot including full-size candy bars, silver dollars and kazoos shaped like Bob Hope’s distinctive ski-slope nose. Dolores Hope reportedly stopped the lavish tradition after chartered buses full of trick-or-treaters began showing up at the house.

Bernstein is quick to point out that a historic designation may not be as limiting as one might think. The distinction may be applied to the home and not the ancillary buildings. Sometimes historical significance can increase the value of the home. Remodels, additions and even demolition may still be possible. There is also no requirement that the home ever be opened to the public.

Both Bernstein and a spokesperson for city councilmember Ryu acknowledge that communication between the city and the Hope family should have happened earlier to avoid the “surprise” that may have led to the unraveling of a sale. Bernstein says the purpose of the 2013 Los Angeles Historic Resources Survey was to allow for “early flagging” of such properties. However, though the information was published on city websites, it was not sent directly to property owners.

Ryu has been out of the country and unavailable for comment. But his spokesperson, Estevan Montemayor had this to say: “I think what happened was, we had put this motion in, and it raised some eyebrows because the communication between ourselves and the property owner was nonexistent.” Montemayor adds that the councilmember acted quickly because “the moment a permit is pulled, we can’t do anything. Councilmember Ryu’s statement is that this is a potentially historic property … we don’t want to infringe on the property owners (but) we want the city to have the opportunity to review it.”