Heart of Darkness

A local writer uncovers a new spirit of adventure in raw and wonderful Papua New Guinea.

-

CategoryTravel

My idea of the perfect vacation is to get lost—go as far away as possible from everything familiar. As a passionate traveler and adventure junkie, I have climbed to the Mount Everest base camp, dived among WWII wrecks in Truk Lagoon, trekked the Amazon jungle. I have assisted in orthopedic surgeries in a converted carpet factory in Katmandu.

But no previous adventure prepared me for the time tunnel that brought me to Papua New Guinea (PNG). There, a precarious balance of 21st-century reality co-exists with Stone Age rituals and some of the world’s most exotic tribes.

Papua New Guinea conjures images of primitive and fierce warriors engaged in headhunting and cannibalism. This is the island where Michael Rockefeller was presumably killed and eaten by locals in the early 1960s.

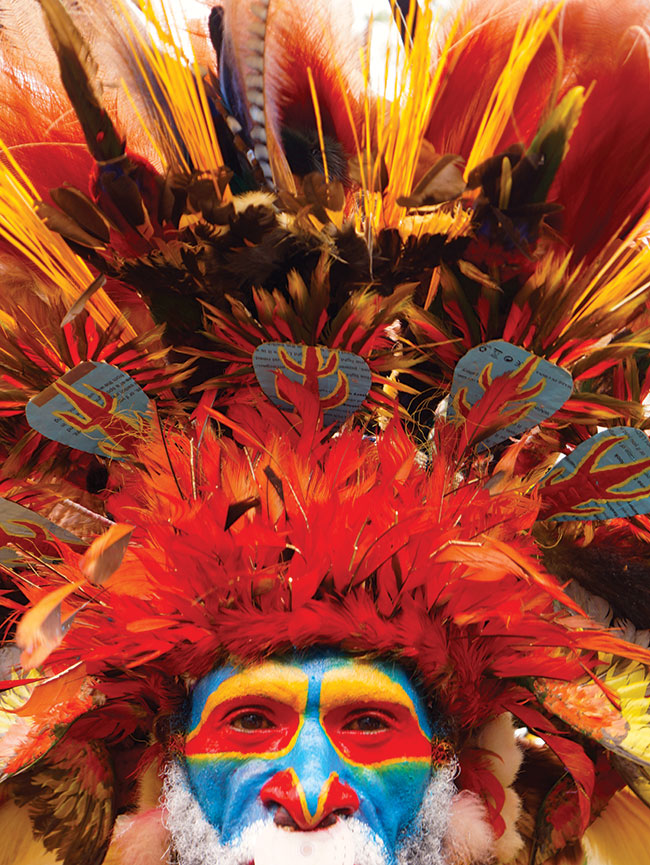

For me, those compelling National Geographic images of spear-wielding tribesman with brilliantly colored face paint and bamboo nose piercings whispered, “Come hither.” It was all so exotic. And while I wouldn’t want to be on the wrong side of a tribal “payback” dispute or the object of a sorcerer’s spell, I was more than ready to venture to this heart of darkness.

Our 10-day journey started in Sydney, Australia, where our group of 13 seasoned travelers met Greg Stathakis, our Santa Barbara-based tour guide. Having led trips for PNG Travel for more than 30 years, Greg was knowledgeable about everything: local customs, politics, what to buy where and for how much! He had cultivated warm and lasting relationships with local people who were keen to share their life stories with us.

Our feet first set down in Port Moresby, the gritty capital of PNG. Port Moresby has landed on quite a few “Top 10 worst” lists due to violent crime carried out by “raskols”—the pidgin term for rampaging gangs. Hotel security guards carrying semi-automatic weapons underscored this dubious distinction.

We were in and out of the capital quickly, but we did enjoy our visit to the National Museum, which houses a wonderful collection of artifacts and antiquities from all over the country. And we enjoyed the impressive Parliament building, conceived as the centerpiece of PNG’s newfound statehood and independence from Australia in 1975.

Our itinerary was to take us to the Sepik River, the heart of food, transport and culture for its local villages and world-famous for the rich variety of artisanal masks and carved figures. Then we would see the lush and mountainous Highlands, the last part of the country to be explored by Europeans. Here, tribal fighting remains a popular pastime.

Our journey through time would culminate with the Tumburu Sing-Sing, an annual, off-the-charts extravaganza of a competition where different tribes parade their traditional costumes, plumage and makeup to the beat of their indigenous music.

For three enchanted days, we journeyed along the Sepik, visiting remote villages along the Karawari and Blackwater tributaries. A nine-cabin riverboat, the Sepik Spirit, served as our comfortable, air-conditioned floating lodge.

Each morning a hardy meal was prepared before we boarded an open-air launch that motored us past cargo-laden dug-out canoes and naked children splashing along the riverbanks. Their parents fished or cultivated sago, a dietary staple from the pith of the ubiquitous sago palm.

Only 300 or so tourists a year venture into the remote villages of the Sepik River Basin, so our visits provoked much curiosity, not to mention a rich opportunity for locals to display their handiwork. This area is considered the cultural heart of PNG and indeed, just when I thought I would not buy a single additional “artifact,” there I was, negotiating “first price” and “second price” (i.e., the final price) for yet another special treasure.

We visited several spirit houses (Haus Tambaran in Tok Pisin)—the ceremonial, spiritual and social center of tribal life FOR MEN ONLY! Happily, an exception is made for tourists.

Craftsmanship is intrinsic to life on the Sepik. Carved, woven and painted pieces are imbued with magical powers of revered ancestors who protect the village from famine, warring enemies and evil spirits. These objects are also central to another Sepik area tradition: The Initiation.

There were constant references to this prestigious rite of passage, and we knew that it was of vital importance for the spiritual wellbeing of the community. But details remained sketchy.

That is until John, our boat captain, held us spellbound as he shared his initiation experience with us on our last night on the boat. Needless to say, it is quite rare for an outsider (and white man) like John to be invited to partake in this sacred group event.

His initiation lasted only two weeks, whereas for most young men it involves enduring several months of seclusion in the spirit house. During this time, they learn their clan’s ancestral secrets, which are passed down orally from generation to generation.

John explained he and other initiates had to abide by many taboos: They could never look at or speak to women during this time; they couldn’t allow the sun to touch their bodies; and they were forbidden to touch themselves in any way (no scratching those pesky mosquito bites). If any one initiate broke any of the taboos, all paid the price—a good flogging.

The initiates also endure taunting and painful rituals that toughen them for life and rid them of any residual femininity. The painful skin-cutting process on both chest and back, which forms keloid scars, mimics the scales of a crocodile, the patron of the Sepik … primeval creator of Earth itself … the ultimate symbol of power and manhood.

I won’t get into the graphic details, but suffice it to say our group was riveted … right up to the point when John took off his shirt and showed us his heavily scarred skin. Certainly not a rite of passage for the faint of heart.

Last stop was Kanganaman, the village at the end of the world. We were accompanied by hungry mosquitoes and curious children on our walk from the shore to the spirit house.

Implanted in the ground close to the entrance of the house were two pointed stones about 3 feet tall, darkly stained at the top. We learned they were Blood Stones, once used to proudly display headhunters’ trophies. The village kids, one dressed in a T-shirt with a picture of Obama, couldn’t wait to have their pictures taken next to these unsettling mementos of the not-too-distant past

I loved the Sepik area and was sorry to leave the river’s tranquility and the gentle pace of life along its shores. But new places and experiences awaited us at our next stop: life at another altitude—the Highlands.

Home for the next few days was at 7,000 feet above sea level. To get there, we took off from a grass field (the local airport) in a 10-seat, twin-engine plane. We flew over lushly rugged valleys and towering limestone peaks to the town of Tari, home to one of the most recognizable cultures in PNG: the Huli Wigmen—straight from the pages of National Geographic.

These strapping men, resplendent in their yellow and red painted faces, ceremonial wigs and leaf skirts, were somewhat intimidating. This was the real deal … not a Disneyland version of “Warriorville.”

Yet despite the enormous cultural gulf, I felt a brotherly warmth. Perhaps my imagination, but I relished the interpretation and took it home with me.

White man first discovered the Highland peoples in the early 1930s. The tribes here are the least west-ernized anywhere on the island, and traditional beliefs rule the day. A man’s wealth and importance is still measured by accrual of pigs, wives and land and is usually the source of bitter tribal conflict.

Each day we ventured into the forest slopes, where the lives of indigenous people are lived as they were 100 years ago. Women do most of the work—raising the children and pigs and cultivating the garden. The men hunt and are the village “soldiers”—stoking generations of tribal conflicts with the time-honored tradition of exacting “payback” (compensation) for transgressions. Tribal fighting is as much about their culture as car travel is to ours.

The Huli Wigmen are all about their celebrated ‘do’s. We went to the jungle beauty parlor to watch young men perform a series of coif-related rituals under the tutelage of a Huli wigmaster. In Huli society, before young men can marry, they must grow a beautiful head of hair, which, at the point of perfection (a full, smooth afro), is clipped and made into a highly prized wig. Add some cassowary feathers and flowers, and you have the renowned Huli ceremonial wig.

PNG traditional society is a culture of male dominance over women. This was especially evident in the Highlands, where the perceived dangers of female substances (especially blood) and sexuality are so powerful, they are thought to threaten male health and masculinity. Women are at once powerful and in need of subjugation.

A Huli village woman talked to us in hushed tones of her previous husband’s abuse (a chronic problem in PNG) and confided that she put a spell on him by adding menstrual blood to a dinner she prepared. He did indeed get sick, and she was released from the marriage. However, she did have to pay back the bride price (a combination of pigs, shell money, flour and rice)—plus interest. Fearing deliberate sabotage by their own wives, Huli men will often take the precaution of cooking their own food.

We had our own up-close-and-personal experience with Highland sorcery. Much to the embarrassment of our hotel manager, three of our fellow travelers had their hiking boots stolen one night. Humiliated and upset, the manager offered a reward for the prized shoes. He also let it be known that if the shoes were not returned, a pig would be slaughtered, casting an evil spell on the culprit. The next person to befall some unpleasant fate (including death) would be presumed guilty and compensation would be exacted.

That did it! The shoes turned up the morning of our departure, exactly where they had last been seen. No pig had to be slaughtered; no spell had to be cast.

Our last stop—and the grand finale—was the Tumbuna Sing-Sing in Mount Hagan in the Western Highlands Province. While there are larger Sing-Sings, the Tumbuna show is one of the most traditional and intimate. Aside from one other tourist group, the rest of the audience was local Highlanders.

Sing-Sings are major cultural events in the lives of the Highland people. The Tumbuna festival celebrates “Taim Bilong Tumbuna,” the time that belonged to the indigenous people. It takes place at a traditional ceremonial ground.

We arrived early to watch the tribes prepare for the spectacle. We were backstage at a fashion show. I watched as they applied bright yellow, red, black and white “war” paint to their faces and the finishing touches to psychedelic headdresses made from human hair, shells, ferns and Bird of Paradise plumes.

I didn’t know where to look first, as a dozen clans in an eye-popping parade, rhythmically dancing to the beat of Kundu drums, proudly showed off their wildly flamboyant costumes. The dances come from different cultural wellsprings.

Some are traditionally performed at Moka ex-changes, a complex system of trade that relies heavily on pigs as currency for status in the community. Other groups of dancers celebrated tribal myths, such as the Mud Men, who wore grotesque clay masks and long, bamboo fingers to appear as returning spirits and frighten their enemies. Body decorations such as shell necklaces and kina shell breastplates were conspicuous displays of wealth.

When the music stopped, we all had plenty of time to whoop it up and interact with our highly spirited Highland wantoks (friends in pidgin).

Day after day I had seen extraordinary things on my trip. But while I was there in the actual vortex, I couldn’t possibly digest the power of the experience.

I was now back home in LA, where a million cars crowd the roads, where hospitals treat the sick, where courts rule on complicated property cases. In the same moment, thousands of miles away in the South Pacific, life goes on.

I couldn’t stop crying. The emotion surprised the hell out of me. While poring over my photographs one day, I was hit by how touched I had been by the warmth and sweetness of these people with the warring persona.