Festival Forgotten

Before Woodstock, there was Newport ’69—LA’s only mega-music festival—held right here in the Valley. The three day event boasted a mind-blowing lineup filled with music legends. Who played, what went down and why you’ve probably never even heard of it.

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written byKirk Silsbee and Linda grasso

Anyone growing up in the late ‘60s remembers the Vietnam War protests, the growth of the drug culture and the popularity of music festivals. The 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, attended by some 90,000 people, ushered in the era of the rock fest, which ultimately spread across the world.

Of course, in 1969 there was Woodstock, the apex of ‘60s mass music gatherings. And just a short year later, the deadly Altamont Speedway Free Festival signaled the shocking finale of the whole thing.

Though seldom acknowledged, the San Fernando Valley made an important entry in that brief epoch. It was called Newport ’69. But despite a jaw-dropping lineup, today the festival is barely a footnote in rock history.

SUMMER SOLSTICE

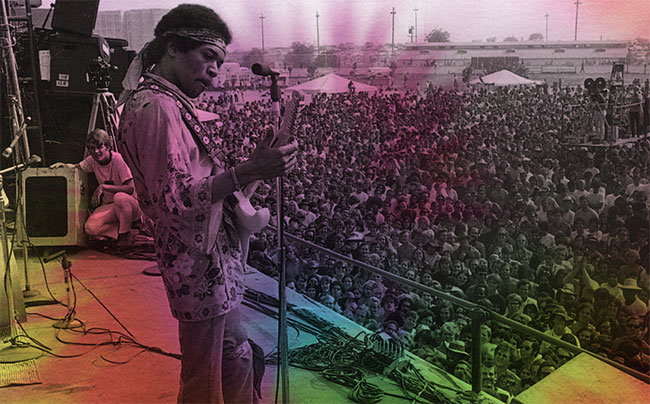

They came for the music. More than 100,000 people—a record number at the time—dropped in to the sun-drenched Devonshire Downs racetrack in Northridge (now part of the CSUN campus) that summer to hear a stellar list performers including Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Creedence Clearwater, The Rascals, The Byrds, Booker T. & the M.G.’s, Ike & Tina Turner, Eric Burdon, Jethro Tull, Marvin Gaye, The Grass Roots, Three Dog Night and Johnny Winter.

Hendrix was considered by many to have given his greatest performance ever. So why doesn’t Newport ’69 have a more prominent place in American music history?

LET’S PUT ON A SHOW

A 24-year-old Stanford graduate named Mark Robinson spearheaded Newport ‘69. “I was a nobody basically. I just loved music,” says Mark.

Originally from Pasadena and now a prominent attorney in Orange County, Mark says he got exposed to music events and Devonshire Downs while in college. Some Stanford buddies got involved with a Renaissance fair at the racetrack and asked him to work as manager.

“Back then, there were these fairs where people dressed up in English costumes from the Renaissance period, and there was live music. That’s where I got a taste of it.”

Then in 1967, the Monterey festival furthered his interest. “That was always in the back of my head. That is what I was hoping to accomplish.”

For Newport ’69, Mark booked 32 groups. “It was pretty simple. I made calls and got groups. I was a novice.”

Before long, the young producer had so many commitments, he had to turn some down, including a legendary band. “Grateful Dead wanted to get in, but I didn’t have room. They called several times. I felt bad. I just couldn’t squeeze them in. They made it big after that.”

Mark’s headliner was Jimi Hendrix—at the height of his career, and he agreed to pay him a whopping $100,000 (an unheard-of amount of money at the time.) He cut deals for between $2,000 to $25,000 for the rest.

Bands were paid from the ticket sales, while Mark funded upfront expenses with $35,000 of his own money and contributions from friends and family.

The audience ranged from teens to college age, each paying $15 for a three-day ticket. The festival, from June 20 to 22, almost sold out. (By comparison, tickets for today’s Coachella Festival typically cost $350 and up.)

The event was held at a time before signage, corporate spon-sorship or giant video screens. At Newport ‘69, it was just about the music.

THE JAM

THE JAM

Friday night opened strong with Joe Cocker, a newcomer at the time. Some press reports indicated he stole the show that evening, even out-performing headliner Jimi Hendrix.

For journalist Harvey Kubernik, there was another high point. He’d just graduated from Fairfax High and has vivid memories. “Spirit blew people’s minds,” he says. “I was riveted by Joe Cocker, but The Edwin Hawkins Singers were unbelievable. That was a hot gospel choir with just a piano that filled the stadium. Janis Joplin didn’t sing, but she came out and said hello to the crowd.”

Steve Fischler, a 19-year-old college student at the time, got a chance to go backstage with his friends, the sons of record company executives. “We did promo work for the festival, passing out leaflets up and down the state. We got as far as People’s Park in Berkeley—for that we got backstage passes,” says the semi-retired manager and publicist. “Everyone was nice, getting high. David Crosby was walking around in his cloak.”

Jethro Tull was what Newport ‘69 stage manager Mark Whaley described as “awesome performers.” Jerry Heller, at the time an agent who represented several of the Newport acts, remembers having to manipulate the timing of Tull’s performance. Scheduled to follow Creedence Clearwater and worried about playing to an empty field (should everyone take off afterwards), Tull’s managers called on Jerry for a favor, wondering if there was any way Jethro Tull could squeeze in before Creedence Clearwater took the stage.

“I went to talk to John Fogerty (Creedence Clearwater Revival) and discussed our business relationship,” says Jerry. “I tied him up long enough for Jethro Tull to play a 30-minute set.” The Woodland Hills resident adds, with a shrug, “That’s the way it goes.”

“It was an incredible opportunity,” says Barry Kaye. Back then he was Newport’s production coordinator. “To think this was the first opportunity where people got to see Joe Cocker and Jethro Tull on stage. They had both just arrived from England. Both ultimately became rock icons,” he remembers.

LA-based band Sweetwater, singular for its cello-flute-keyboards-conga instrumentation, played on Saturday.

“I enjoyed the show a lot. It was home, after all,” shares Nancy, the lead vocalist, who is from Glendale. “We were accustomed to playing shows like that far away from home, so it was cool to be right there.”

Sweetwater keyboardist Alex Del Zoppo adds, “It was one of the few times we were able to enjoy a festival without having to rush off for another booking.” Sweetwater went on to be one of the first bands to take the stage at Woodstock.

Mark Rodney, who was a teenage roadie for several San Francisco bands, got there on Sunday. “I rode in with this English guy in his Mustang,” he says. “He drove right up to the backstage area and told somebody that he was with one of the bands, and we walked right in. Three steps away from the car, and I was in the backstage area with all these cool people, smoking a joint with Jimi! You could do that then; it was really a magic time.”

TURBULENT TIMES

The magic mood changed, however, on Sunday. On the final day, crowds of teens—without tickets— had gathered outside the fence and were cutting it to sneak in. Although a professional security agency had been hired for the event (at a cost Barry Kaye remembers as being in the $30,000 range), and the LAPD was on site all weekend long, more security was needed. Some fraternity houses from USC volunteered to help, as well as some people from a car racing enthusiasts club called the Streetracers.

In local newspaper reports at the time, concertgoers are quoted as saying a raucous melee broke out after one teenager threw an orange at a police officer. The officer reportedly chased the teen, inciting other kids to begin throwing fruit and bottles at the LAPD. Some officers reportedly began swinging billy clubs. The chaos, according to media reports at the time, resulted in dozens of (minor) injuries.

Mark Robinson vehemently disputes those accounts. He says he was watching when the teenager threw the orange and—other than seeing the police officer chase the young man—nothing else happened. “Any reports of injuries and police hitting people are simply untrue.” He does say that Sunday changed the mood at the event. “For two days we’d had no police reports. Everything was fine, and then there was this.”

Barry Kaye, now a chiropractic neurologist, also downplays Sunday’s incident. He views the problems as stemming from what he calls the “love-in mentality.”

“You had a group of people,” he explains, “who thought they were entitled to having music for free. But the festival really was a cultural phenomenon. And this group of teens on Sunday was pretty small when you compare it to the thousands who attended throughout the weekend.”

There were also reports of recklessness; business owners complained that concertgoers littered the area, trashed public bathrooms and even stole items. Neighborhood associations also got upset at the trash, noise and crowds.

Those were the aspects of the concert that made headlines—completely overshadowing the performances. “The part that made the press,” says Newport producer Mark Robinson, “was unfortunate. It was too bad no one ever talked about the great music and the crowd.”

HENDRIX MAKES HISTORY

Jimi Hendrix, as it turns out, also got lost in the mix, despite turning in what is considered by some music historians to be one of his best sets ever. He first hit the stage on Friday night. Just returning from Toronto for a pre-trial hearing for drug charges—which would inspire him to write the sardonic “Room Full of Mirrors”—he was in a foul mood. It was a short, listless set.

“Thirty-three minutes for $100,000,” Barrymuses darkly.

Mark took action. “I called his manager and asked if he’d come back. Hendrix was a class act.His manager agreed to do it.”

At Sunday’s comeback, the artist more than vindicated himself via a two-hour, improvised jam—especially on a scorching version of “Red House,” his psychedelic blues. “From what I understand, some of his band members later said it was their best performance ever,” he shares.

LEFT IN THE SHADOWS

Despite Hendrix’s stellar performance, the killer line-up and the historic crowds, Newport ’69 is rarely mentioned in music history. Mark believes it’s simply a matter of being overshadowed by a better, bigger story.

“Woodstock was a free music festival where people camped out on a New York farm for days. It rained, and people stayed, and that aspect of it became a national news story,” he says.

Barry agrees. “The really iconic moment in time was Woodstock. All these people came together. It rained. But people had a really good time.”

And, there was more drama at the New York festival. Two people died; one from a drug overdose and another person was accidentally run over by a car.

Furthermore, Hendrix died just weeks after Woodstock, adding to that festival’s mystique. While the organizers of Woodstock worked ardently to promote it, ultimately making a movie with the footage, for Mark, promotion—during or afterwards— was never a goal.

“I was working throughout the festival. My 14-year-old brother probably saw more than I did!” He adds, “I may have a few old photos in some boxes, but I’d have to look for them.”

The month after Newport ‘69, Mark enrolled in Loyola Law School. Although he lost money on the endeavor, he insists he has no regrets.