Change Maker

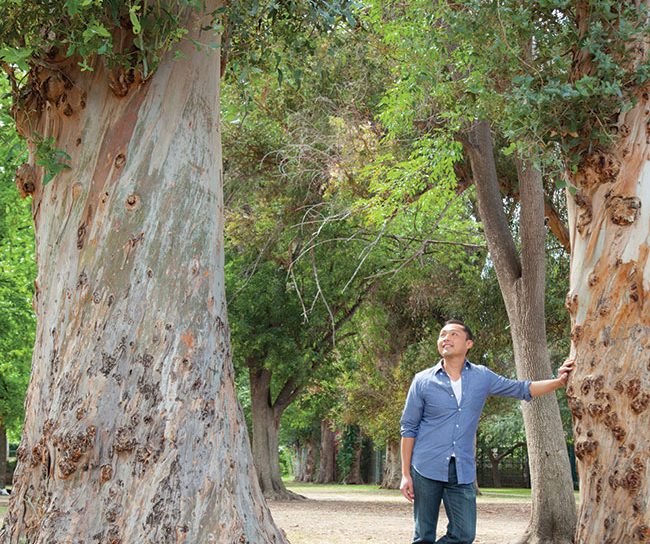

He may be known as an über-successful Malibu developer, but a major focus for Richard Weintraub in recent years has been a Valley landmark.

-

CategoryPeople

-

Written byMichael Goldman

The real estate magnate, responsible for projects like Malibu’s high-end Lumber Yard shopping center, has his sights set on on transforming the Sportsmen’s Lodge events center and surrounding site into a retail complex. Here he addresses his motivations and why, amidst the uproar, he feels he’s fighting the good fight.

As the portraits of long-gone luminaries, such as Clark Gable, Marlon Brando, John Wayne and others, hover over him during lunch at the Sportsmen’s Lodge Patio Café, Richard Weintraub is eager to discuss the hopes, dreams and frustrations surrounding his ongoing efforts to remake the Studio City landmark property where such Hollywood legends used to cavort. As we enjoy our meal on a hot summer day, one can’t help but recall that era’s vibe: movie stars, goldfish swimming in channeling waterways, politicians visiting and historical meetings happening.

Weintraub is intimately familiar with that history and visited the hotel often as a child and teenager with his mother, longtime LA school board member Roberta Weintraub. But now he says it’s time for an updated twist on a more classical form of a retail center … and not the “mega mall” that some folks seem to think he is pursuing. It’s a center catering to the area’s expanding, younger, affluent demographic in particular.

He makes a comparison to the old Northridge Fashion Square, back in the day. “You know that feeling of why people came to the Valley in the first place—it was for open spaces,” he says. “You could park, walk around and have that Wonder Years experience. is about trying to create a sense of place—what I call an outdoor living room—to attract younger people who may not drive as much anymore, or who bike, who want to go somewhere and sit and have a great coffee, meet friends for dinner, work out at a gym, and take a walk along the LA River. That kind of feeling is what Fashion Square was in its day. I want to recreate that sense here.”

On this particular day, Weintraub, 48, a Malibu resident and married father of two, is also enjoying reminiscing with his longtime friend and advocate—Los Angeles political consultant and lobbyist Steven Afriat—about Sportsmen’s Lodge’s rich pedigree and various memories from Weintraub’s own journey toward becoming a prominent Los Angeles developer.

Weintraub is Afriat’s client, but they have known each other since the developer was a teenager attending political events at the hotel with his mother. Afriat insists that Weintraub doesn’t fit into the standard build-it-and-they-will-come developer stereotype.

“My experience with Richard, and I’ve known him a long time, is that he is about what he wants to leave behind,” Afriat says. “ has not been a money-maker for Richard. He won’t say that to you. But he does love owning the Sportsmen’s Lodge and wants to do something special with it.”

Indeed, while Weintraub has fond recollections of Sportsmen’s Lodge, like many Valley residents, he holds an unwaveringly forward-looking view about what needs to happen next with the hotel he now owns (and remodeled in 2013), along with the adjacent events center and surrounding property. (Weintraub holds a long-term lease on the property upon which the hotel sits.)

It’s a chunk of significant real estate Weintraub has been angling for almost a decade to redevelop into an open-air, multi-use, shopping and dining “outdoor living room.” The development, to be renamed Sportsmen’s Landing, is slated to be a 97,800-square-foot, $60 million overhaul of the property that will require tearing down the events center and surrounding the hotel with a 40,000-square-foot Equinox gym, 20 retail shops, five restaurants and children’s play areas.

Weintraub’s vision has wound its way through the approval process, and earlier this year the South Valley Planning Commission turned down a series of appeals—giving a green light. The Studio City Residents Association declined to oppose his efforts, and he has support from the Studio City Neighborhood Council, the Chamber of Commerce and the Business Improvement District, among others.

But the plan is not without opponents, ranging from locals worried about traffic and parking issues to those wanting to preserve the events center as a historical site. At this point, the biggest obstacle has become the New York-based family that owns the hotel property grounds. They are suing Richard to break his longterm lease on the hotel land, alleging—among other things—that they are not satisfied with his plan’s parking study.

Although he is a Malibu resident, Weintraub stresses he is also “a Valley boy” who is “completely self-made, 100% on my own.” His father is Dr. Lewis Weintraub, whom Weintraub proudly declares still practices proctology three days a week in Encino at the age of 91. He grew up in Sherman Oaks, attended Birmingham High and was basically raised with “real estate and entrepreneurship running in my blood.”

“From my mother and grandmother , I was taught to fight for what you believe in and to always work to make your community a better place,” he says. “That is really important to me. And my dad also followed his passion, which was medicine. He just wanted to make people feel better, to give them good care. They taught me to fix something, make something, create something and do something.”

His first job was at the age of 14, working for a relative in real estate. By the time he went off to Pepperdine, Weintraub had worked for George Moss Industries in Encino and hustled individual residential listings on his own as an 18-year-old. After graduating from Pepperdine and earning his MBA from USC, he started buying apartment buildings and eventually broke through as a developer with the Venezia residential building along the Wilshire corridor in the mid-1990s.

His company, Weintraub Real Estate Group, has since been involved with several prominent projects—including the 30,000-square-foot Malibu Lumber Yard retail center, built in partnership with Richard Sperber, and the restoration of LA’s former St. Vibiana’s Cathedral into a modern event facility. But Sportsmen’s Landing, he says, has been “the most difficult project of my career” because of the fact that, although he has all the approvals he needs, due to the lawsuits it is unclear when the project will go forward.

All of which Weintraub finds ironic, because he has a clear fondness for the facility’s history and firmly insists the project requires community collaboration. But he also believes in looking forward and not back.

“I came into owning the property in 2007 ,” he says. “Then the great recession started almost immediately after that. We did a remodel of the events center in 2009 as a mid-term way to generate income while we figured out how to redevelop the property ethically. But the events center, for how people do events today, is really antiquated—almost a dinosaur. Everything is laid out incorrectly. The scale is wrong to make a real go of it like that. I know the history, and we all get upset when something great changes. But people sometimes tend to remember ethereal ghosts of the past.”

Over the years Weintraub has strategically branded himself as a “community-oriented developer.” He recently joined the board of the LA River Corporation and emphasizes that Sportsmen’s Landing will have a beautification component for a portion of the river directly behind the complex, highlighting “open spaces.” He insists his entire philosophy about development is to “harness the history of a property and not try and overbuild.”

In Malibu, for instance, he points out that he pivoted on a proposed resort hotel development after hearing community concerns regarding local traffic patterns. Instead he reimagined the project entirely, transforming it into a quieter concept: the Malibu Memorial Park project—a proposed nondenominational chapel, cemetery and memorial facility. Malibu city manager Jim Thorsen, who worked closely with Weintraub on the Lumber Yard project, supports the developer’s claim of wanting to collaborate with communities.

“Not only from a financial standpoint for the city but from an environmental standpoint, it’s been a great private-public partnership where we teamed up with an individual who built a commercial facility that also, in the long run, benefitted the water quality in our region ,” Thorsen says. “Working with him was a win-win situation for everybody.”

And that is, to a large degree, the root of Weintraub’s argument regarding Sportsmen’s Landing—that everyone could win if they all worked together.

“We now have the chance to do something special—what I call neighborhood retail,” he says. “A lot of retail in Studio City and Sherman Oaks has fragmented ownership, and it is hard to create a critical mass of stores, because different people own little slivers here and there. That makes it hard to redevelop in most places. On this site, we can do that in keeping with where the neighborhood is going. This plan was created in consultation with the community, and we are building to significantly less than half of what we were allowed under this specific plan. And we are generating a project that will have about $100 million a year in sales tax revenue and bring in well-paying jobs. And we will still have beautiful event space—beautiful gardens and one 2,000-square-foot room and another 1,000-square-foot room. But some people are calling all that a mega-mall, unfortunately.”

Regarding traffic and parking, Weintraub says those issues were addressed in the plan in great detail and approved for him to proceed, with provisions existing to reconsider future concerns that may crop up along the way. Other aspects of the opposition center on the site’s historical significance; some locals insist that it simply needs some adjustments to attract more business—not a complete re-do.

Take Charles Gherardi, for instance. He resides in Sherman Oaks, just a few minutes from Sportsmen’s Lodge. He has heard Weintraub speak to the Sherman Oaks Homeowner’s Association and has nothing bad to say about Weintraub or, in fact, any developer “wanting to develop any property he owns.”

“But on the other hand, many of us tried to get this property safe from development but we were turned down regarding making it a historical site . I’ve been going there for decades and can only speak to the joy the Sportsmen’s Lodge has brought to my family. We had a 25th anniversary party there, for example.

I’ve taken my entire extended family there for Easter brunch. We’ve had young kids there enjoying the pony rides and petting zoo they’ve had there . For decades it was a thrill seeing the rainbow koi swimming around the pools there. My feeling is that if they did the things that were there before but enhanced the existing property, they could still make a profit. My point is, perhaps he has not made good use of what there is there now to make it profitable, and perhaps he could expand on the facility itself without .”

Weintraub carefully differentiates between local opponents like Gherardi and what he describes as strategic attempts from a small group to “wear me down.” He recounts obscene messages left on his cell phone and having his daughter present for the five-hour South Valley Planning Commission Meeting in April while some “personal” things were directed his way.

He also appears visibly disturbed while discussing the petition this past summer to try to recall board member Lisa Sarkin from the Studio City Neighborhood Council for allegedly advocating on the project’s behalf in her capacity as chair of the council’s land use committee. The petition was rejected by a 13-2 vote. Weintraub has strong opinions about where many of those specific efforts are coming from; he claims they are directly connected to the hotel-property lawsuit, although opponents have denied that in press reports.

GRAND PLANS An artistic rendering of the proposed Sportsmen’s Landing complex, which would be adjacent to the recently renovated hotel.

But overall he continually returns to advocating ongoing, direct interaction between himself and the local community. Indeed, he suggests folks with questions or concerns should just contact him directly, pointing out that he is “no corporation without a face” and is happy to talk to anyone with honest interest in the project on either side of the issues. He insists he is “easily reachable,” and “we’ll set up a time and take your call.”

Alan Dymond, president of the Studio City Residents Association (SCRA), agrees that Weintraub has actively pursued community input. He adds that the SCRA thoroughly examined Weintraub’s plans and simply could find no reason to oppose them.

“The SCRA is not a homeowner’s group—we represent all residents of Studio City: renters, condos, homeowners, everybody,” Dymond explains. “Richard originally came up with some proposals and worked hard with Lisa Sarkin. She looked at them, we looked at them, and there were serious concerns about the location, the height of the buildings, stuff like that. Richard listened to us and went back and made adjustments in accordance to what we were suggesting. Basically his final proposal did incorporate our suggestions. Keep in mind the property is zoned for commercial development, so really he could develop as he wished as the owner, with all entitlements in place. So he really did not have to listen to us, but he did.”

As lunch winds up, an associate tells Weintraub that it’s time for his photo shoot. “I hate getting my picture taken,” he exclaims. As he gets up from the table, he is asked if he will allow himself to be worn down, or if he will see the Sportsmen’s Landing saga to its ultimate conclusion.

“I’m trying,” he says. “It’s not easy. I have a lot of debt associated with it and a lot of stuff to deal with. But I’m doing my best, I really am.”