The Big Business of Making Babies

Would-be parents are flocking to Encino, the latest hub of reproductive services.

-

CategoryHealth

Written by Anne M. Russel, Illustrations by Christine Georgiades

Valley residents struggling with fertility used to head over the hill when seeking assisted reproductive technologies (ART). But nowadays there is a plethora of fertility centers—some of which are nationally acclaimed—right in our own backyard. Encino has become something of a hub for fertility treatments for LA and beyond, with at least five major ART facilities, as well as a surrogacy specialist, located within the town’s boundaries.

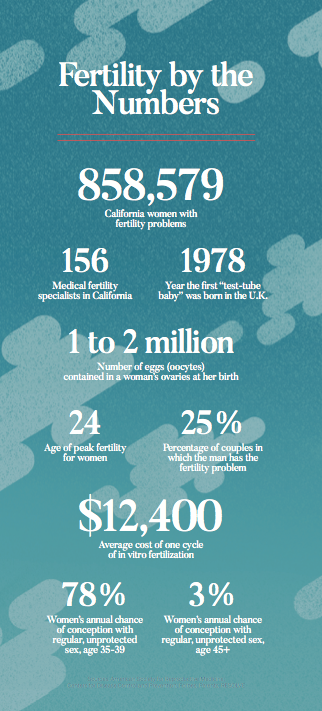

Why the boom? Diana Duenas, CEO of the Encino Chamber of Commerce, sees it this way: “Encino is an affluent community that’s centrally located in the Valley. Encino’s name has cachet to it.” Citing statistics from last year, Duenas puts Encino’s average household income at $154,444 and, equally important, says 27% of its population is in the age 35-54 range, which is ART’s sweet spot.

Fertility specialists with Encino offices include the California Center for Reproductive Health, Fertility & Surgical Associates of California, the Fertility Institutes, HRC Fertility and the Los Angeles Reproductive Center. The U.S.’s relative lack of regulations on reproductive services make it a magnet for wealthy medical tourists from more restrictive countries, such as Australia and Japan, or countries where socialized medicine sets treatment limits, such as Canada. And since China eliminated its one-child policy, there has been a boom in older Chinese couples traveling to Southern California for help adding to their families.

Seeking medical intervention for conceiving a child means getting sucked into a tornado of medical acronyms, starting with ART itself. Quickly following that are specific ART service options with names like IUI, IVF and PGS. Tamara*, a 37-year-old photographer who has been trying for five years to conceive with her husband of seven years, remembers her first encounter with a fertility doctor as being disturbing and confusing.

She did one unsuccessful treatment cycle at that clinic—which cost her $18,000. Unhappy with that outcome, Tamara then went, she says, “doctor shopping.” She is now working with a different facility, trying intrauterine insemination (IUI), a form of artificial insemination in which the doctor transfers “washed” sperm into the uterus via a catheter. (“Washing” means that the healthy sperm is separated from seminal fluid and weaker sperm prior to use.) In Tamara’s case, the IUI is done after a round of drugs to stimulate ovulation. Of the various forms of artificial insemination, which also include ICI (placing the collected sperm at the cervix, the neck the uterus ) and IVI (inserting the collected sperm into the vagina), IUI has the best success rate. It is a great deal cheaper than in vitro fertilization (IVF), which requires retrieving eggs from the woman’s ovaries, combining them in laboratory glass-ware (in vitro is Latin for “in glass”) with sperm, incubating the fertilized eggs, and implanting the selected embryo in the woman’s uterus.

Dr. Mousa Shamonki, a board-certified specialist in both OB-GYN and reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Fertility & Surgical Associates of California (FSAC), notes that sometimes less is more and that jumping to the most aggressive treatment isn’t the right approach for every patient. “Sometimes it’s more appropriate to do less,” he says. “Sometimes the right thing to do is nothing if the couple hasn’t been trying long enough.”

Dr. Shamonki, who is also an associate clini- cal professor at UCLA, emphasizes however, that it’s important to nd a specialist you feel comfortable with, since conception problems

can have multiple causes and multiple solutions. “The problem is the unknown,” Dr. Shamonki says. “It’s important to have an ongoing conversation about considering other options.”

BabyMaking 3.0

BabyMaking 3.0

Especially for women over 40, the options Dr. Shamonki mentions include implanting an embryo produced from a donor egg (fresh or frozen) fertilized with the male partner’s sperm or even using an embryo left over from someone else’s IVF. In that case, of course, the baby born from the procedure doesn’t share any DNA with either parent.

Lisa,* a 40-year-old data analyst, suffered through two unsuccessful IUIs and a false pregnancy before deciding to push ahead with the much more costly IVF. Speaking for herself and her husband, she says, “We just figured it was the last chance, so if it was going to be $18,000, we were just going to go for it.” Plus unlike 90% of ART clients, Lisa was fortunate to have health insurance that covered the cost of some of the procedures and all of the drugs.

She ended up with four embryos from her own eggs on the first IVF cycle: two girls and two boys. She and her husband decided to implant one of the female embryos and now have a healthy, full-term baby girl. They haven’t decided what to do with the remaining three embryos. “I’m not there yet,” Lisa says. “We’re just going to leave them frozen for now.” Options include donating to someone else (“too weird,” says Lisa), throwing them out, designating them for medical experimentation or trying more pregnancies.

Dr. Michael A. Feinman, a board-certified fertility specialist at HRC Fertility, which ranks in the top five clinics nationwide for success rates, says that determining the vigor and gender of embryos accurately is one of the major refinements since the early days of “test-tube babies.” Known as preimplantation genetic screening or preimplantation genetic diagnosis, PGS and PGD allow doctors to grade the fertilized eggs for their viability—and that has boosted success rates and reduced complications.

“The embryo selection processes have improved,” Dr. Feinman says. “We used to have to ‘stuff the ballot box,’ hoping one would be normal, but now we can cut back

on the number of embryos we implant.” That, in turn, has cut the frequency of multi-baby pregnancies, a condition that can threaten the health of both the mother and the fetuses and can result in lifelong developmental problems for the children. “I can’t remember the last triplets we had,” Dr. Feinman says happily. Now when a multiple birth results from IVF, it’s usually because the fertilized egg split in half naturally, resulting in identical twins.

Another ART method that has seen significant improvement is egg storage. “Freezing techniques are excellent now,” says Dr. Shamonki. “You don’t lose eggs the way you used to. You can keep eggs and embryos frozen indefinitely.” Dr. Feinman concurs, noting that the oldest embryo he has successfully implanted was 13 years old. Of course, no one knows how long “indefinitely” really is, but Dr. Feinman jokes that the freezers “would probably survive a nuclear war.” He adds, “The tanks are quite solid. There’s no known time limit for cryopreserved embryos.”

Egg freezing (cryopreservation) is a growing business for fertility clinics, as women increasingly get the message that fertility is relatively short term and that it peaks early (age 24) and begins shutting down around age 30. By going through a cycle of treatment with fertility drugs and having multiple eggs retrieved (typically two to three per cycle using drugs that stimulate ovulation), a young woman can ensure that she will have healthy, viable eggs for fertilization and implantation when she decides later in life she is ready to have a baby.

The general consensus among reputable U.S. practitioners is that the cut-off point for carrying a baby is age 55. Says Dr. Shamonki, “I don’t want to put the woman at risk. But even if you take pregnancy out of the equation because they’re using a surrogate, there is a ceiling in terms of human longevity.”

Dr. Shamonki cites the famous case of the 66-year-old Spanish woman, Maria del Carmen Bousada, who gave birth in 2006 after IVF treatment at a clinic on Los Angeles’ Westside. She died less than three years later, leaving her twin boys motherless. “You have to have concern for the unborn child,”he says.

The Building Boom in the Valley for Senior Living Communities Has Escalated

Upscale livin’ for active retirees.