A Group of Holocaust-era Violins Is Helping to Spread Hope & A Powerful Message

Never again.

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written byAnne M. Russell

Note:

Due to the Coronavirus, all the Violins of Hope performances this spring have been cancelled. They are working on rescheduling for January 2021.

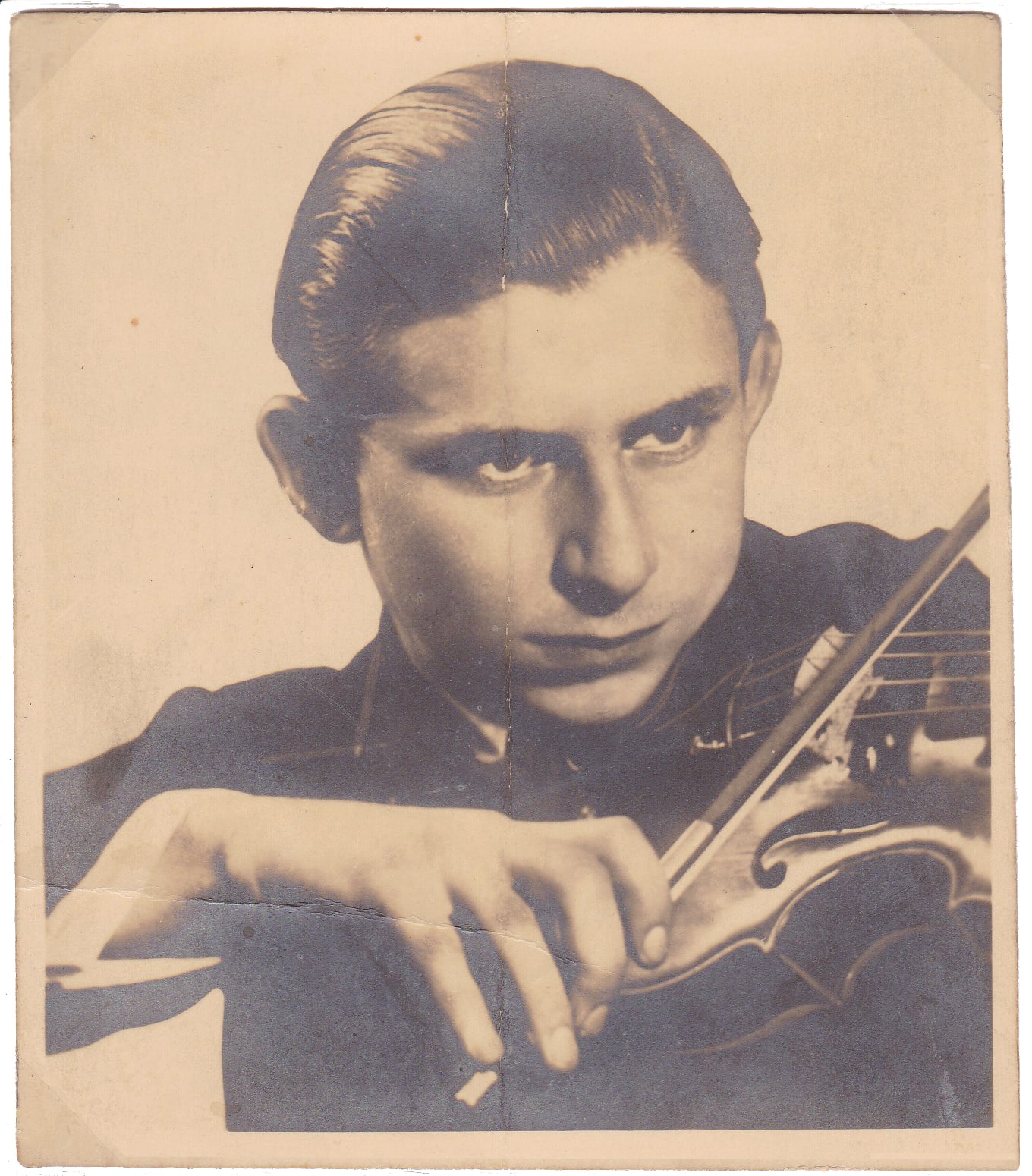

Zvi Haftel, the first concertmaster of the Palestine Orchestra, later to become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. He was one of about 100 musicians gathered by Bronislav Huberman all over Europe in 1936 and brought to Palestine. Haftel’s violin is one of the best in the Violins of Hope collection.

If you talk to Holocaust survivors and their families, it will inevitably come up. It is by far their most pressing concern. As the passage of time silences the voices of Holocaust survivors, who will speak for them? Who will keep the memory of the Third Reich’s atrocities alive as a warning to future generations about the consequences of hate?

The Weinstein family is hoping their family’s collection of historic violins will help fill that void. The Weinsteins’ ambitious program, known as Violins of Hope, features 87 violins, violas and cellos that survived the Final Solution; many of their owners did not. Sixty of the instruments are in playable condition. The three-generation family of luthiers—skilled craftspeople who build and repair stringed instruments—still run a shop in Tel Aviv, Israel. The shop was founded in 1938 by Moshe and Golda Weinstein after the couple emigrated from an increasingly hostile Eastern Europe.

In March and April, California State University Northridge’s performance center, the Soraya, will host three concerts featuring the best of the instruments. The first concert, on March 22, will be led by Los Angeles Jewish Symphony conductor and founder Noreen Green, and will feature soloist Lindsay Deutsch on one of the restored violins. “Hearing music played on these violins will have a hugely emotional impact,” says the conductor of her concert, which will include selections from the score of Schindler’s List. “But I don’t want people to only feel sad; I want them to say, ‘We’re alive. We’re still here.’”

EDUCATING THE NEXT GENERATION

At the same time, CSUN’s Soraya Arts Education Program is reaching thousands of local schoolchildren. The program kicked off last summer with some 40 workshops for teachers in conjunction with the Holocaust education nonprofit Facing History and Ourselves. The workshops were aimed at helping teachers prepare classroom content about the Holocaust suited for various grade levels, starting with elementary schoolers. The teachers then provide historical context for what the students will experience during the visit from the Violins of Hope team.

Culminating in six daytime performances at the Soraya in March, the Violins of Hope school program will ultimately serve as many as 4,000 students from Valley, Glendale and Compton schools. The school arts outreach is an annual effort, but, says Soraya education director Anthony Cantrell, “This is the longest and most ambitious program we’ve ever run. And we’re hoping it’s the most impactful.”

After Shimon Krongold died during the Holocaust, a survivor brought Krongold’s instrument to his brother in Jerusalem. The violin and a picture of Shimon holding the instrument are the only items of Shimon’s legacy that survived the Holocaust.

HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

On a sunny day in January, just three days shy of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp in Poland, about 50 teens gather in the cavernous band room at Cleveland Charter High School in Reseda. Cantrell and the Soraya’s artist in residence, violinist Niv Ashkenazi, are visiting. Ashkenazi carries with him one of the recovered violins, a beautiful instrument crafted in the early 1900s in what was then Yugoslavia. On its back: a shining Star of David inlaid in iridescent abalone shell. The violin’s previous owner escaped Nazi Germany to Israel, bringing the instrument with him where eventually it found its way into the Weinsteins’ collection.

The students sit silent and solemn as Cantrell and Ashkenazi talk and play songs, including “Tradition” from Fiddler on the Roof (which only a handful of students acknowledge having previously heard) and the true story of a Jewish boy’s heroism from the book Violins of Hope. Ashkenazi complements Cantrell’s reading of the tale of how Ukrainian teenager Motele Schlein used his violin case to smuggle explosives into a Nazi officers’ club with a poignant composition by Julius Chajes, a Jewish composer who fled Austria for the U.S. in 1938.

At the end of the performance, Cantrell tells the students, “You are the hope for the future to make sure those ideas [of the Nazis] don’t take hold. Celebrate the idea that there’s a humanity connecting you.” Some of the music students come up to thank Ashkenazi, while others hurry on to their next class. Did the words and music make an impression on them? Music teacher Cameron Yassaman is certain that they did. “When the bell rings and nobody moves, that’s as powerful as you can get. They were pretty locked in,” he says.

And that, in a nutshell, is the Weinsteins’ goal, as third-generation luthier Avshalom Weinstein explains: “I want people not to forget the stories and the people and our very, very recent history.” Avshalom and his father, Amnon, still repair and restore violins and other stringed instruments in their Tel Aviv shop, although the extensive U.S. tour, of which the LA visit is part, is taking up considerable amounts of their time. Avshalom hopes that his son will follow the family trade for a fourth generation, but says, “He’s only 6 years old right now, so it’s going to take a while.”

Above: Violinist and Soraya artist in residence Niv Ashkenazi

BEYOND THE CHORDS

Although grandfather Moshe was the one who began the collection of the historic violins, it was Avshalom’s father, Amnon, who conceived the notion that the violins should spread the message of “never again.” The very first violin in the collection came from a Jewish refugee who could no longer bear owning a German-made instrument emblazoned with the name “Wagner.” Although the Wagner who crafted the violin and Richard Wagner—Adolf Hitler’s favorite composer and a vocal anti-Semite—were unrelated, its owner found it was too painful a reminder of the Third Reich, and sold it to Moshe.

That owner’s experience is by no means unique. Says Thor Steingraber, executive director of the Soraya, “Most of the people who escaped with their violins never played them again,” due to a complex mix of survivor’s guilt and bad associations. Some owners owed their lives directly to their instruments, since they survived Auschwitz by playing in one of the Nazi-approved bands or orchestras there, even making music to drown out the cries of victims in the gas chambers at the demand of the camp guards.

What is it like to play an instrument connected to so much tragedy? Ashkenazi, who has spent two and a half years with his entrusted violin, says that there’s a give and take—that it isn’t only the artist who changes in response to the historic instrument, but that the instrument changes too. “There’s a different connection with this instrument,” he says thoughtfully. “Constant playing keeps the violin alive. You hear the voice of the instrument open up. I try to put myself aside and let the voice of the instrument come through.”

Steingraber says that being aware of the violins’ history, and hearing their voices, is “very powerful and very memorable. When you’re in a concert hall, there’s a collective reaction, there’s a strong community bonding.” Adds Green, “I always say Jewish music is the universal language. It hits you in the kishkes; it hits you in the guts.”

Join the Valley Community