Walk into Charles Fine’s studio in Inglewood, and you’re immediately struck with its size and scale—ceilings impossibly high, light in excess—followed by the visual enormity of the art that graces it. Though this is very much a working artist’s studio, the space feels and looks like a high-end gallery. On display throughout are Charles’ monumental creations, all grounded fundamentally and symbolically in nature.

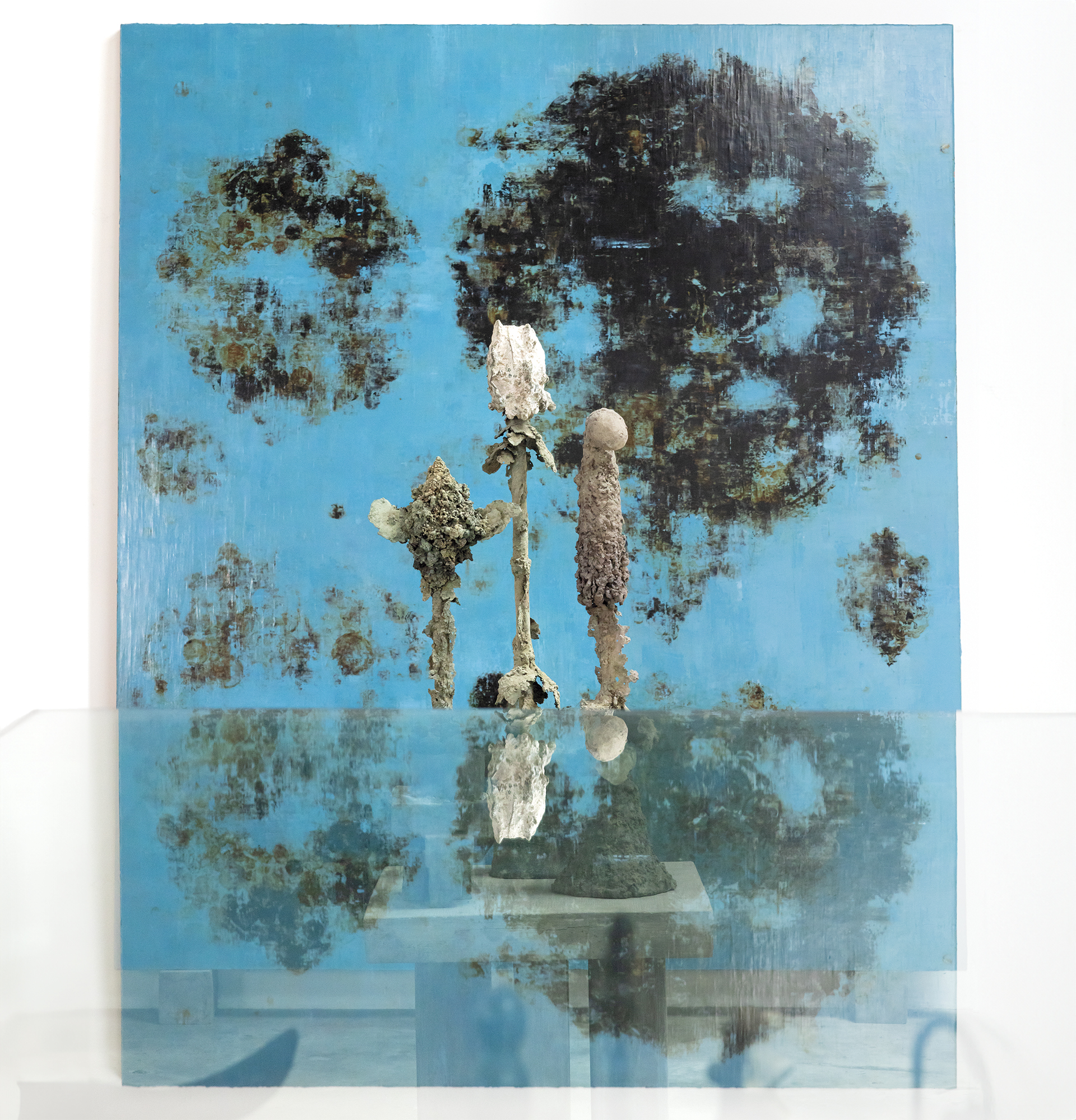

Charles next to an original plaster sculpture that was used to cast three bronze versions. It was inspired by “an inch-long appendage that grows in Pacific Ocean kelp beds.” Of the tall structure in the foreground, the artist says it is “open for interpretation. Growth, living structure and regeneration come to mind.”

“My work deals with how histories inhabit the present,” is how Charles explains it. “The histories I’m referring to are environmentally related. And how that environmental thought translates into form.”

In multiple mediums over the past half century—painting, sculpture, drawing, photography and video—this nature-based connective tissue runs throughout, as if one piece is a natural extension of the other. Whether it be his showstopping Table of Contents—a series of large metal and glass viewing tables that display fragile, organic found objects; or his bronze sculptures, some freestanding, some wall-hung—the experience is visceral and poetic. You find yourself wanting to touch them, to experience their sensual, organic shapes firsthand. His paintings similarly draw you in. Though they seem abstract at first glance, a deeper look reveals that they too appear to be an extension of and inspired by the natural world.

“My initial thought was to create a body of work that not only referred to the natural world and living structures, but one that also acknowledged ever-increasing environmental issues and the psychological state they perpetuate. I felt then, and still do, that this thought is all-inclusive, as we inhabit this one planet, together,” Charles says.

A prolific creator since the early 1980s, Charles has had numerous one-man shows, most notably at the internationally recognized Ace Gallery here in LA (closed in 2016), and in New York and Mexico City. His final show at Ace Gallery, “A 30 Year Survey,” spanned 14 rooms and 33,000 square feet. His work is also represented in several private and museum collections, including LACMA, the Orange County and Santa Barbara Museums of Art, the LA-based Frederick Weisman and Marciano Collections, and the Andrea Nasher Collection in Dallas. Among Fine’s public works: a monumental bronze sculpture that graces the entrance to the AKA Beverly Hills (hotel) on Crescent Drive in Beverly Hills.

Although the artist’s fascination for all things organic stems in part from his travels to places like South America and Mexico, his preoccupation with natural forms and the pursuit of visual detail started here in the then-rural and verdant San Fernando Valley.

“The Valley of my youth (he was born in 1951) was rich, endlessly interesting, and utterly insular. It was nature-filled and safe. A world unto itself.”

Charles’ first childhood home was on the border of Encino and Sherman Oaks on Firmament Avenue. As the artist describes it, it was “just down the street from Liberace’s house on the corner of Valley Vista and Sherman Oaks Avenue. The cluster of houses beyond that would soon be destroyed via eminent domain, making way for the construction of the 405 Freeway.” After the creation of the first Sepulveda on-ramp, Charles and his boyhood friends would ride their bikes up that ramp and onto the just-paved freeway, which was not yet open to traffic. They would “sail like the wind all the way to the Sepulveda Dam, where we’d ditch our bikes and explore the rain overflow tunnels, full of frogs and tadpoles. And from there to the cornfields where Balboa Park now resides.”

“My work deals with how histories inhabit the present. The histories I’m referring to are environmentally related. And how that environmental thought translates into form.”

A few years later, Charles and his family moved to a property on Encino Avenue. “It was a large, deep lot, full of every kind of fruit-bearing tree you could imagine. Plums, citrus, apricots, peaches … I climbed every one of those trees at least a thousand times.”

His boyhood also included some more-refined Valley experiences. In 1955, Charles’ father, Don Fine, and his uncle, Raymond Fine, bought the famed Sportsmen’s Lodge. The Fine brothers expanded the popular hot spot into what soon became a star-studded gathering place. Charles remembers riding from Encino to Studio City in his father’s Jaguar XK120, top down rain or shine, whizzing down Ventura Boulevard, past the blinking neon of the movie houses and watering holes.

“There were no sidewalks, and as you approached Coldwater Canyon, the Boulevard was flanked by massive, old-growth trees. Like a forest to either side.” When they arrived at Sportsmen’s Lodge, they’d enter the massive porte cochere, where if it happened to be a Sunday, Howard Hughes’ limousine would be parked. The phobic billionaire and producer would wait with whatever starlet had caught his fancy until his meal was delivered to him through the car’s window.

Three of Charles’ “Furnace Flowers” sculptures, with the oil on canvas painting “Elemental Forces” in the background.

But it wasn’t the stars or the infamous that fascinated Charles. Rather, it was the Garden of Eden-like wonderland that stretched to the banks of the LA River beyond the lodge’s massive walls of glass at the back. It was here that Charles would explore the trout lakes, waterfall, the dense and mysterious jungle of mature trees—the essence of which remains apparent in all of his work to this day.

Another location in the Valley helped form Charles’ artistry: the classroom. His first stop was Hesby Street Elementary School in Encino. “My teachers would set up little easels, and we’d paint outside under the shade of the trees for what felt like hours.” It was about that time that his mother signed him up for an art class outside of school. “It was in a little shack on a huge, wild lot in Sherman Oaks that Mosel Oglesby, a self-declared beatnik, taught me about oil paints. I was 7 years old.” Then on to Mulholland Middle School, where he honed his skills in industrial drawing, drafting and woodshop class that helped to form his sculpting skills. And finally, Birmingham High School in Van Nuys.

“That’s where things began to get real,” he recalls. “I took classes in advertising and album cover design and illustration. In 1969 I entered a competition that LAUSD held every year. I won the #1 prize with a Black Power poster. Power to the people! I still have it to this day.”

Against the blissful backdrop of his childhood, troubling events were brewing in the world. “Smog and the Vietnam War,” he recalls. As the pollution that gripped LA (and particularly the Valley) in the 1970s escalated, so too did the war. To avoid the draft, Charles left the paradise that was his childhood home. Though he would eventually return, putting down roots here once again, his childhood experience would continue to make an indelible mark on his body of work.

“Growing up in the Valley left lasting impressions on me—the interface of a burgeoning metropolis and the remnants of its natural past,” he says. Today, when reflecting on the Valley, the artist can’t help but take a pragmatic viewpoint. “With the last orange groves and cornfields came development and the onslaught of traffic and stifling smog. Fortunately, the smog has been abated, but definitely not the traffic!”

Join the Valley Community