The Long-forgotten of the Women Who Worked Manufacturing Rocket Engines at Rocketdyne in the 1950s

Before their time.

-

CategoryPeople

-

Written byChristina Rice

-

Images courtesy ofThe Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection

-

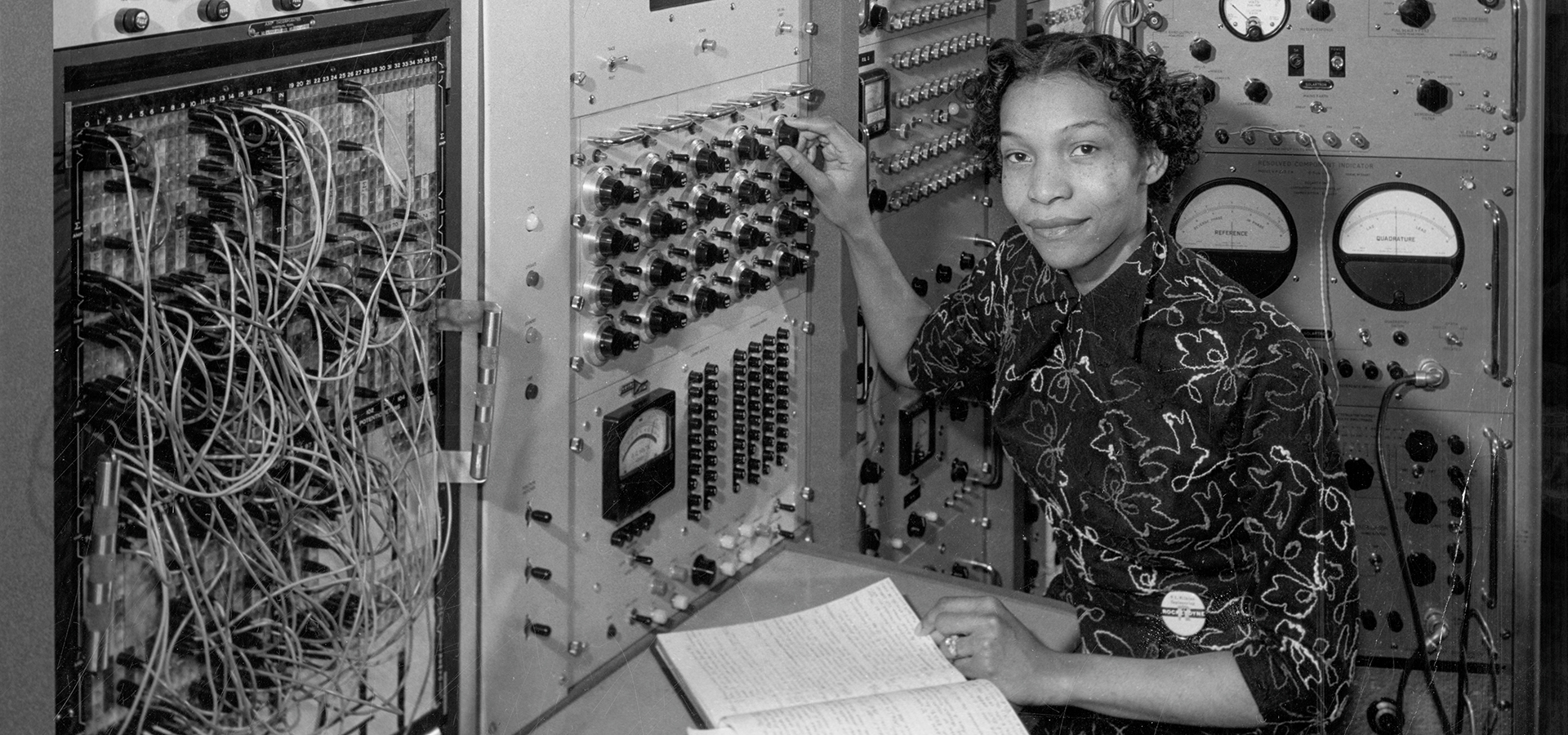

Rutgers University graduate Norma Sutton of Van Nuys was a research chemist. She was part of a team of scientists who analyzed the fuel that powered rocket engines.

Above

It’s hard to imagine today, but after World War II, women, who had sustained the American workforce during the height of the conflict, were encouraged to embrace a life of domesticity and return to the family home. This was also the period when Southern California emerged as the aerospace capital of the world. Fields such as math and engineering, cornerstones of the industry, had always been male-dominated, but the gender gap became even more pronounced during this time.

Above Betty Edwards of Canoga Park was a graduate of UCLA with a degree in engineering. She designed the installation of electrical utilities throughout Rocketdyne facilities in the Valley.

•••

While there may have been a dearth of women employees at the companies supporting the country’s space race-fueled ambitions, they were not completely absent. In recent years, books such as Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly and Rise of the Rocket Girls by Nathalia Holt have brought to light the careers of women at places such as NASA and JPL. Rocketdyne was another juggernaut of the aerospace industry.

Specializing in the development of liquid-propelled rocket engines, Rocketdyne came to prominence in the Cold War era, and the facility at the corner of Canoga Avenue and Victory Boulevard remained a San Fernando Valley fixture for nearly 60 years. It and a field laboratory in the Santa Susana Mountains provided jobs to thousands of Los Angeles residents, reaching a peak of more than 20,000 employees in the mid-1960s during the country’s frantic space race against the Soviet Union. Rocketdyne served as a key supplier of rocket engines for NASA, including those used for the Apollo program that ultimately landed American astronauts on the Moon in 1969.

Above Nasira Wilkins was graduate of Howard University with a master’s degree in physics. She was a rocket scientist at Rocketdyne, studying liquid propellant rocket engine concepts.

•••

Rocketdyne opened its Canoga Park headquarters in 1955 and described it in newspaper recruitment ads as “the most modern and complete facility of its type in the Free World.” It anticipated staffing of around 4,000, including “engineers, technicians, skilled craftsmen, and administrative personnel.” A mere four years later, the facility had expanded to accommodate three times that number of active employees. Roughly 18% of them were women. In highlighting this minority workforce in January 1959, the Valley Times referred to Rocketdyne’s female population as the “Canoga Rockettes,” noting that they “have more precision than their dancing counterparts in New York City, and here it’s not a chorus line, but an assembly line for rocket engines.”

Setting aside the flip comparison to Radio City Music Hall’s fabled dancers, the Valley Times piece provides a fascinating statistical breakdown of close to half of Rocketdyne’s female workforce at the time, which numbered 2,260. Included in the reporting were engineers (12 women of 1,500 total engineers), assembly workers making “little black boxes” (43), blueprint librarians (30), production control clerks (20), inspectors (30), engine assemblers (14), artists and illustrators (132), welder (1), milling machine operator (1), plating equipment operator (1), sheet metal layout specialist (1), stenographers (262), accounting clerks (more than 100), keypunch operators (50), blueprint machine operators (30), and typists (410). Additional jobs assumed by women included brazers, drill press operators, tube benders, tool crib attendants, expediters and electrical test mechanics.

The newspaper would go on to feature more Rocketdyne women in subsequent years. The women’s names aren’t remembered today, but the fact remains: The women of Rocketdyne helped propel Americans to the Moon and beyond.

Join the Valley Community