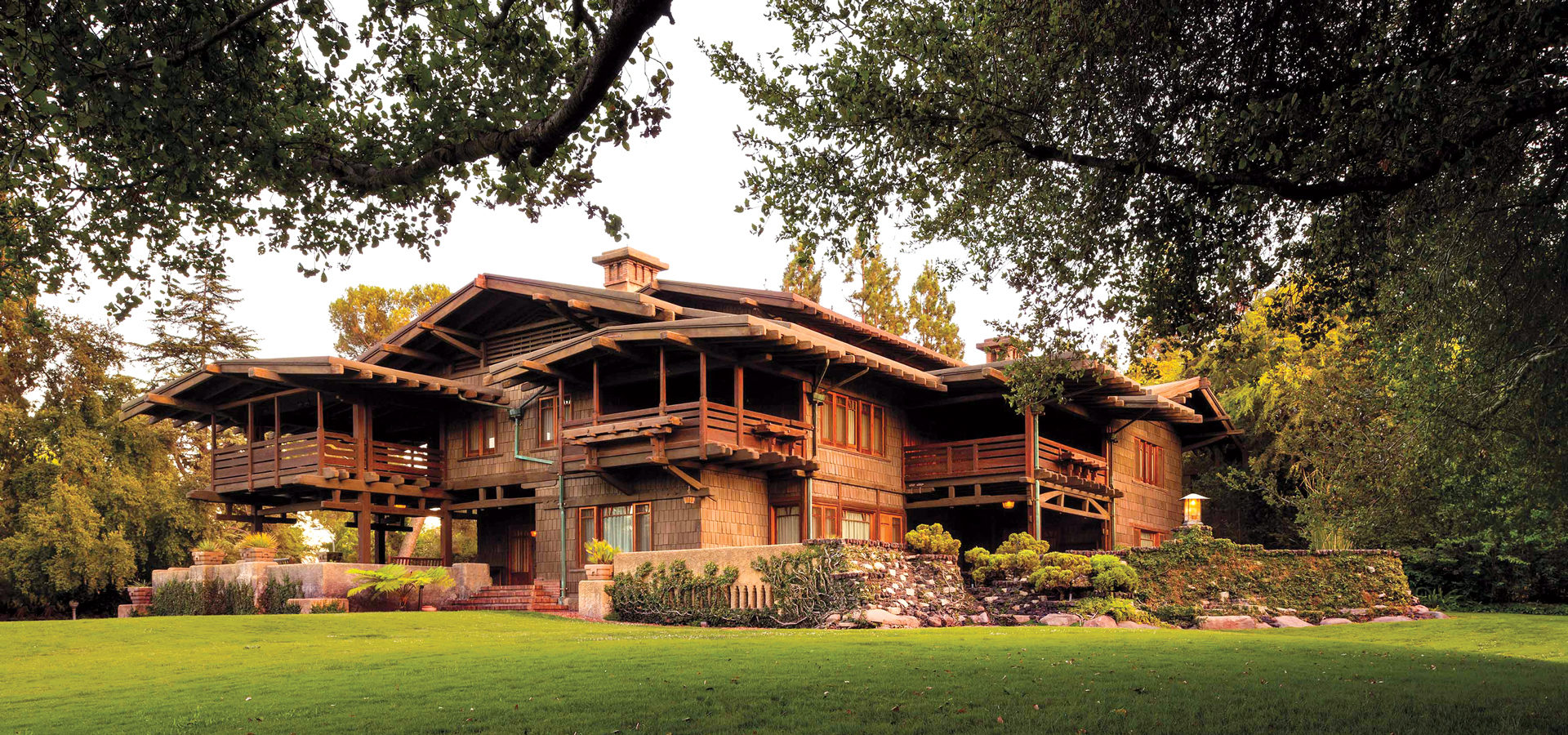

Upon first glance, you might not notice Japanese influences in the design and architecture of The Gamble House, Pasadena’s stately and historical Arts and Crafts landmark. But with a guided eye, details come to life, from a stained glass tree on the front door that resembles a Japanese black pine to the pagoda-like appearance of the low-slung roofs.

Above: The Gamble’s entry features a stained glass tree on the front door that resembles a Japanese black pine.

•••

Brothers and architectural partners Charles Sumner Greene (1868–1957) and Henry Mather Greene (1870–1954), who established their esteemed firm Greene & Greene in 1894, designed this National Historic Landmark and California Historic Landmark, considered one of the finest examples of Arts and Crafts architecture in America.

“They were influenced by ancient wood-building cultures, but they were building in the moment of 1908, and trying to create something entirely new and beautiful and appropriate.”

From afar, it is easy to mistake the 8,100-square-foot building for a museum. But Greene & Greene designed it as a single-family home, built in 1908 for Procter & Gamble heir David Gamble and his wife, Mary, as a winter residence away from their home in Cincinnati. The brothers carefully consulted with the couple to add elements of grace and craft, according to Edward R. Bosley, executive director of The Gamble House. Those elements include several Japanese design features, including the small pond on the back patio that reinforces the Shinto idea of integration with nature, and the asymmetrical rear view that reflects the Buddhist conception of wabi-sabi, or finding beauty in the imperfection of nature.

The Greenes first began learning about Japanese architecture and design as students at MIT—then located in Boston—which they attended from 1888 to 1893. “Indeed, all over Boston, Japan was in the air, and the Greenes were breathing it,” Bosley says.

After their graduation, the Greene brothers proceeded to tour a variety of Japanese design wonders. They attended the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, viewing the Ho-o-den, or Phoenix Hall, a scaled-down version of the Ho-o-do Temple in Japan, which inspired what Bosley calls “a generation of Japanese-esque houses built in the (Phoenix Hall’s) wake.” In 1894, they visited the Midwinter Exposition in Golden Gate Park, where they toured the Japanese Hagiwara Tea Garden. And in 1901, Charles and his wife, Alice, visited the Pan-American International Exposition in Buffalo, New York, where they witnessed the Japanese Midway Exhibit.

As the story goes, Charles was summoned in 1904 by client Adelaide Tichenor to the St. Louis World’s Fair to see the building at the Japanese Imperial Garden which, she shared, was composed of many types of wood. Supposedly, no two types were from the same tree. “I do not want you to go on with my home until you see the Fair,” she wrote to him. “You will be able to get so many ideas of woods and other things for finishing what you now have on. It will be impossible for me to describe to you the effect of the woods.” That visit resulted in a Greene-designed structure for Tichenor with clear Japanese inspirations: various types of wood coexisting in harmony, a tile Irimoya roof, and a garden courtyard featuring a half-moon shape.

Bosley points to the wood structures of The Gamble House to illustrate how the Greenes were influenced by other wood-building cultures, including China, Korea, Switzerland and Japan. From the Douglas fir structural timbers to the redwood exterior shingles to the Burmese teak panels and mahogany furniture and paneling in the living room, building in wood was a central part of the Greenes’ philosophy, as in Japan. “They were influenced by ancient wood-building cultures, but they were building in the moment of 1908, and trying to create something entirely new and beautiful and appropriate,” Bosley notes.

Above: The dining room at the Gamble House

•••

The Greenes’ inspiration from Japanese architecture wasn’t limited to sourcing of building materials. Craftsmanship was viewable to the naked eye in the American Crafts movement, and that was reflected in the exposed outdoor beams that fit perfectly together, buttressing outdoor sleeping porches. Beyond the porches, a view of the gardens and landscaping showcased Japanese-style natural harmony.

“Where the Greene’s architecture really excels is that it did not ignore the landscape around the houses—on the contrary, it was very conscious of it,” Bosley says. Though clients sometimes complained that it took the Greenes too long to decide where in the landscape to place a house, the pair were determined to carefully consider views of the house from a number of perspectives, as well as how the house connected to the land. In the case of The Gamble House, the architects considered the home’s relationship with not only the immediate landscape, but also the surrounding landscape of the San Gabriel Mountains and the Arroyo Seco.

To Bosley, the pond on the rear patio is clear evidence of Japanese influence on The Gamble House. “The stones in the pond have surfaces that rise above the surface of water,” Bosley explains. “These become stepping-stones in the pond itself, a feature you see in some Japanese gardens.”

Even before The Gamble House, Charles Greene had become curious about Japanese design and incorporated it into several other homes. He had purchased Edward Sylvester Morris’ book Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings, showing how foundation stones were pounded into place. “This was apparently a revelation for Greene and had an immediate impact on his work,” Bosley says, referring to stone feet Charles later designed for posts at the Arturo Bandini house in Pasadena and the Cora Hollister house in Hollywood.

Bosley also points to the 16 carvings at the frieze level of the Gamble House’s living room—carvings that are similar in concept to panels in Japanese homes called ramma.

As shaped as they were by Japanese architecture and art, the Greene brothers wrote little about how Japanese style influenced them. “They weren’t very forthcoming about why they did what they did,” Bosley concludes. “Their work speaks for them most eloquently.”

Join the Valley Community