CSUN’s Herbarium of Ancient Specimens Becomes Part of National Study

The secrets of plants.

-

CategoryPeople

-

Written byAnne M. Russell

-

Photographed byJames Hogue

At California State University Northridge, in one of the newer science buildings, there’s a closet stuffed full of thousands of dead plants.

Student Destini Kananipour examines a specimen card.

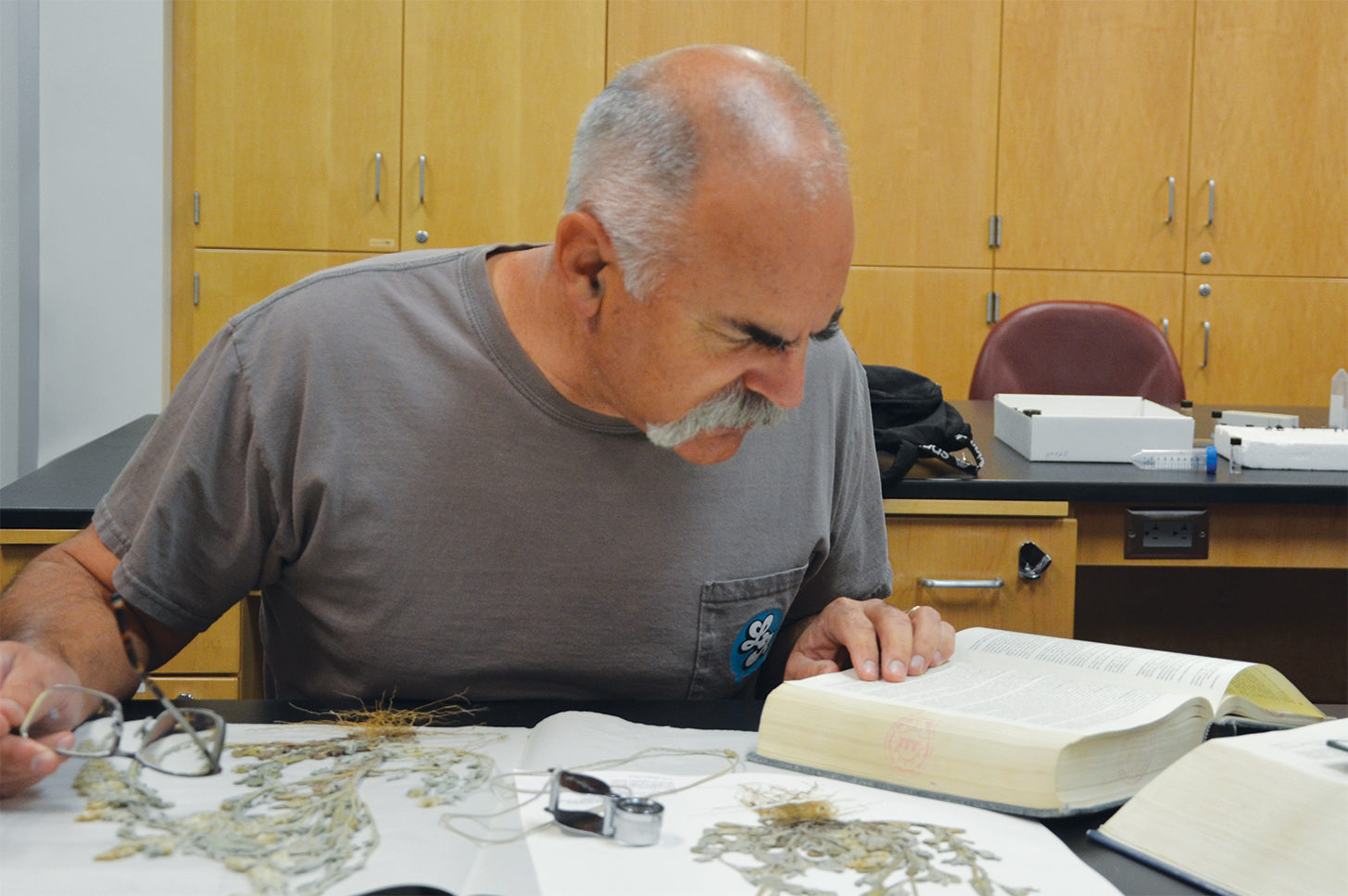

Known as an herbarium, that collection of dried, pressed plants is an invaluable and irreplaceable resource for students and researchers of many disciplines, as well as curious amateur botanists. “This is a library,” says James Hogue, who has been collections manager since 1996, “but instead of books, it’s objects.” And, while previously little known outside the university, the herbarium in Chaparral Hall is now accessible to millions of people worldwide, thanks to an online database known as Integrated Digitized Biocollections, or iDigBio.

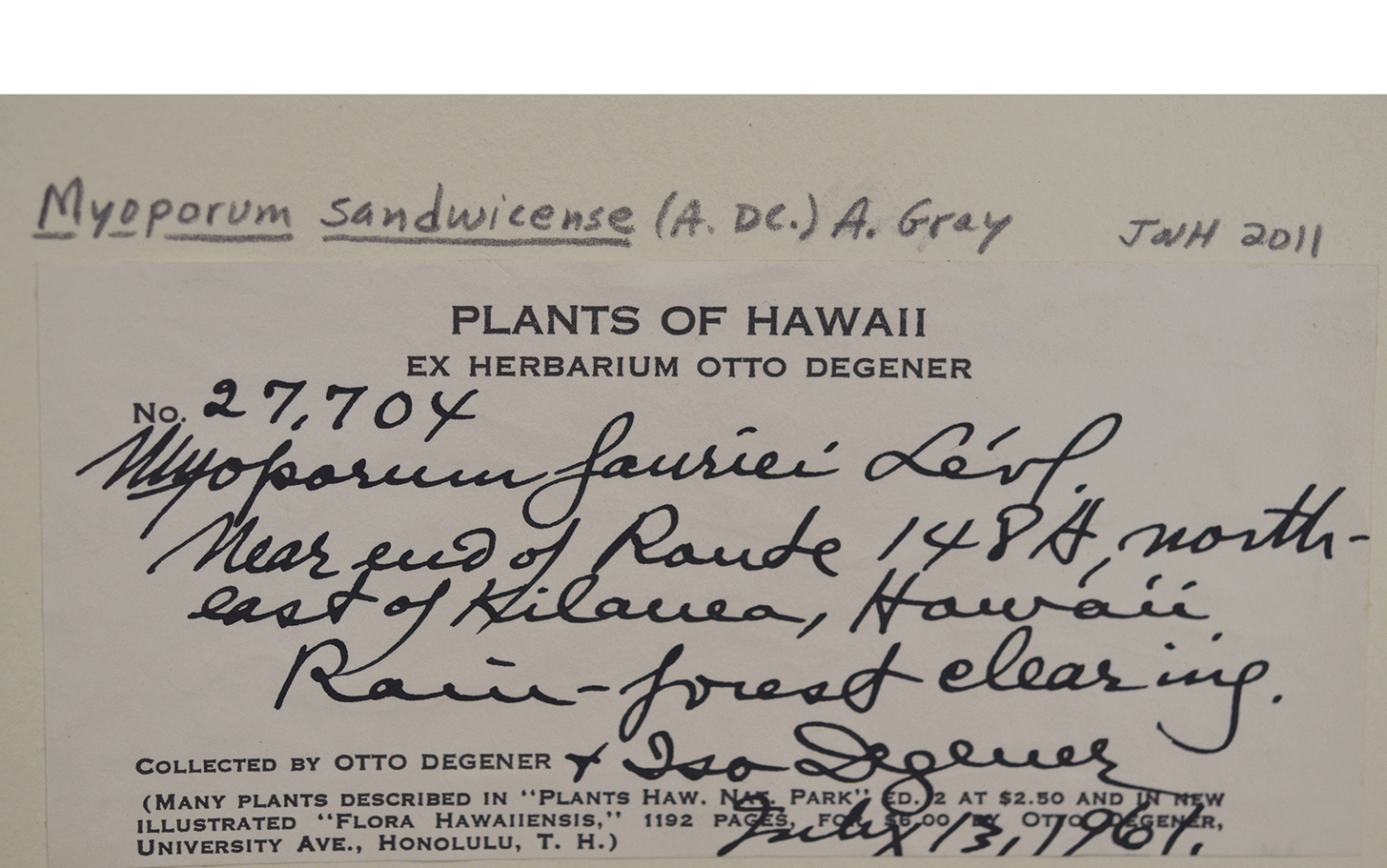

The database was made possible when the National Science Foundation put up $100 million for the 10-year Advancing Digitization of Biodiversity Collections (ADBC) initiative. CSUN received $33,000 to add its small California-focused herbarium to the massive project that has so far digitized 1,000 collections of birds, bugs, fish, fossils and plants. It took Hogue and students working under him more than a year to get through 25,000 specimen cards. “The images are so good,” says Hogue, “it’s like having the specimen in your hands.”

“It democratizes collections that people didn’t have access to before,” says CSUN professor of terrestrial ecology Paula M. Schiffman, Ph.D. “Now, anyone can explore all sorts of collections everywhere.”

The label from a false sandalwood tree collected in 1961 that was reclassified in 2011.

Digital Disaster-Proofing

Schiffman notes that there’s an important secondary benefit to creating a digital repository of images: “Herbaria are really vulnerable. There’s fire and insects and other disasters that destroy specimens.” While CSUN itself was established in 1958, its herbarium contains specimens that are more than 200 years old, because—in the spirit of scientific collegiality—herbaria around the world cooperatively trade and gift specimens.

After the 1994 Northridge earthquake, Dr. Schiffman recalls, the herbarium was temporarily off limits while the CSUN staff waited anxiously to learn whether the building where it was then housed had survived intact. (It had.)

An older earthquake story that sends chills through every collections manager concerns the fire following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that almost completely destroyed the California Academy of Sciences’ extensive herbarium. Alice Eastwood, the Academy’s heroic curator of botany at the time, climbed into the badly damaged and soon-to-be burning building to save 1,000 “type specimens,” the term for the first record of a new species. All others were lost.

A more recent botanical horror story involves the 500,000-specimen herbarium at the University of Louisiana at Monroe (ULM), which came close to ending up in a dumpster. The collection, the largest in the state, was housed in a stadium field house that the university wanted to renovate. In 2017, university management set an “or-else” deadline of midyear.

At the last minute, the Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) in Fort Worth stepped in to rescue the doomed herbarium. BRIT noted in a statement at the time, “The ULM collection represents more than 99% of the species in Louisiana’s vascular flora. Its loss would have seriously impaired botanical scientific research not only locally within Louisiana but also nationally and even internationally.”

Fortunately, the enormous collection’s specimen sheets had all been digitized at that point thanks to ADBC, although not all the associated data had been attached. It is an ongoing effort, says BRIT collections manager Tiana Rehman. She notes one other upside to digitizing these orphaned herbaria that are now stored far from their home turf: “Digitizing these records is a way of repatriating collections.”

“This happens over and over again,” says Hogue, sadly, of the evicted herbarium. “We always have problems with money. We always have problems with space.”

Coral bells from 1898.

Big Data Goes Botanical

Both Hogue and Schiffman teach field classes that take students outside to botanize, a practice that has changed little since Gherardo Cibo came up with the idea of collecting and preserving plant specimens in 1532 to create the world’s first herbarium. (Astonishingly, some of his collection still exists.) Hogue describes collecting expeditions humorously as, “You just rip the plants up like you are making a salad,” meaning that collectors take specimens roots and all. The plants are then laid flat between sheets of newspaper until they can be put into a press to be arranged and dried properly.

But what has changed dramatically is how iDigBio’s 127,899,469 specimen records can be analyzed—which is what makes this initiative critically important. Director for Research at iDigBio Pamela S. Soltis, who is also a distinguished professor at the University of Florida, explains: “One example of how these records are being used has to do with forecasting how species will respond to climate change. Using the locations where specimens were collected, coupled with information about temperature, precipitation, and elevation, we can project where the species might occur in the future under different models of minimal to extreme climate change.”

Once that modeling and analysis is complete, Dr. Soltis says, “This information can help guide conservation strategies, agriculture, and more.” One such strategy is known as “assisted migration,” in which land managers like the National Park Service move seeds and tree seedlings to cooler, higher elevations to save them from rising temperatures. Farmers, too, need to plan their climate-change response as the environment grows hotter and drier (or, in some areas, wetter) and will no longer be able to sustain certain traditional crops.

Collections manager James Hogue.

Digitization’s Darkside

You might expect only positive consequences of this kind of widespread knowledge sharing, but as always with technological innovation, there is a downside: plant theft. As the California Native Plant Society notes, “Plant poaching is a serious problem that puts dozens of species at risk every year. Succulents like Dudleya, orchids, cacti, and carnivorous plants are regularly stolen from wildlands and sold on the black market.”

To date, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has prosecuted four criminal cases and made other arrests of succulent stealers, who are estimated to have poached hundreds of thousands of native Dudleya (sometimes called liveforevers) valued at tens of millions of dollars.

Of iDigBio, Hogue says, “People who steal plants use these data too. That’s a reality when you make your data available to the world.” Specimen records are so specific that they essentially provide a street address for would-be thieves, which has led iDigBio to make certain digital specimens accessible only on request.

Still, Hogue is optimistic about iDigBio’s larger impact. “It’s enabling more people to participate in science. I think it makes them appreciate it more.”

Join the Valley Community