King of the Jungle

The inside story of literary legend Edgar Rice Burroughs and his lasting legacy on one of the Valley’s most prominent towns.

-

CategoryUncategorized

-

Written byWillard Simms

If you live in the Valley, you’ve probably reflected at one time or another on the rather eclectic mix of town names: Reseda, Encino, Sylmar and Van Nuys, to name a few. But on the unusual scale, Tarzana takes the cake.

Tarzana? What kind of name is that for a town? Sounds like Tarzan shouting his famous yell at the end of his own name: Tarzan-aaa-aa-aaah!

You might be surprised to discover that Tarzana actually does come from Tarzan, or more specifically from the creator of Tarzan: Edgar Rice Burroughs.

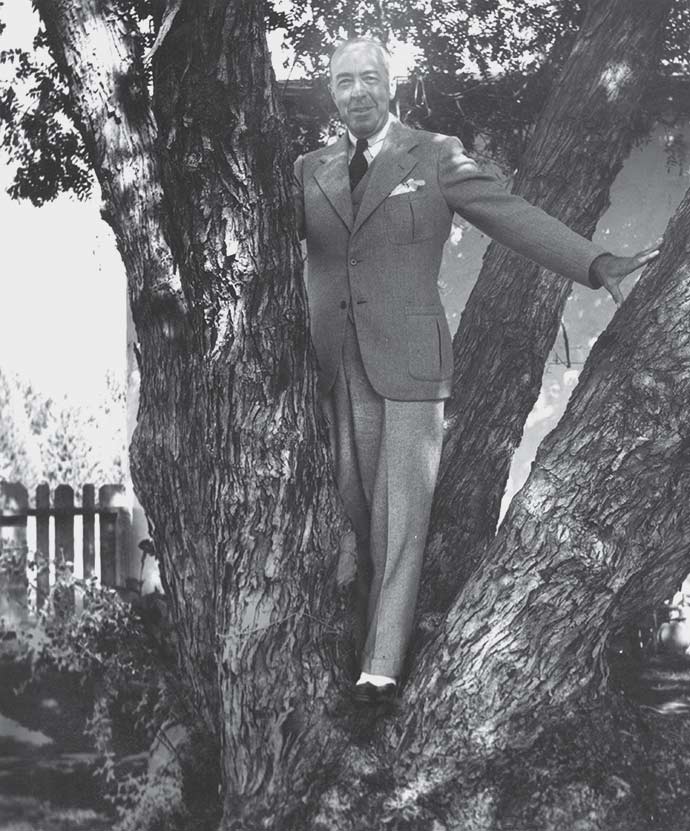

Beginning in 1919, the writer was the owner of almost all the land that we now know as the community of Tarzana. Burroughs bought the 550-acre property from LA Times founder and publisher, General Harrison Gray Otis, for $120,000 and named his new property Tarzana Ranch, after his immortal creation, the King of the Apes.

As the story goes, Tarzan, who first appeared in the novel Tarzan of the Apes, was raised by apes. After he discovers the world of men, he chooses it over the apes, learns several languages and eventually takes his rightful place in England’s House of Lords. But he ultimately decides to reject that life and return to the wild as a heroic adventurer.

Tarzan of the Apes, which established Edgar’s career in fiction, was written elsewhere. But many of the 24 Tarzan books, published over the course of his lifetime, were created at the estate where he lived with his wife, Emma, and three children: Joan, Hulbert and John.

Tarzana Ranch, as Edgar called the property, was quite extensive, running the length of what we now know as Reseda Boulevard, bordered by Mulholland on the north and Ventura on the south. The land that later became El Caballero and Braemar County Clubs also were part of the Burroughs estate.

The main dwelling, where Edgar and his family lived, was located on a hilltop near what is now the corner of Reseda Boulevard and Tarzana Drive. Otis Drive, the one-time single-lane dirt road originally put in for General Otis, dead-ends near the base of the former mansion.

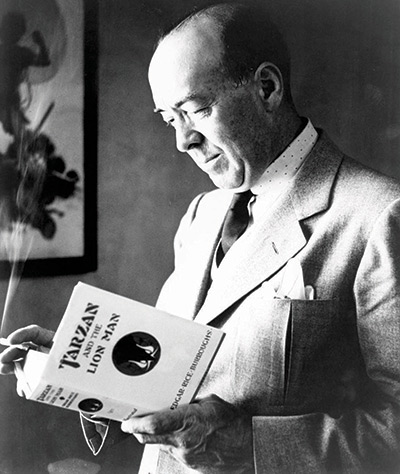

The writer flips through one of his 24 Tarzan novels.

Besides the formidable main house, the estate included servants’ quarters, an orchard, a hunting lodge, a dairy, horse stables, a detached ballroom and a pool big enough for Johnny Weissmuller (the actor who played Tarzan in many of the films) to swim laps in. John Burroughs, Jr., E.R.B.’s grandson, remembers as a child throwing rocks at the exotic fish that lived in the outdoor pond and hiding in the secret panels hidden in the walls.

You wouldn’t call the character of Tarzan even mildly provocative now, but when the character first appeared, he was quite a jolt to the collective consciousness. Essentially, he was the first all-American, half-naked hunk! So instead of being just a series of novels about an ape-man, he was a cultural sensation at the time.

And Edgar set out to capitalize on it in every way possible: through a syndicated comic strip, movies, a radio series and lots of merchandising. Talk about having a nose for business—he even got the rights to the Tarzan yell that Johnny Weissmuller made famous.

You might wonder who would buy such a thing. Slot machine manufacturers, for one. Every time a patron hits a jackpot on a Tarzan slot machine in Las Vegas or at a Native American casino, Tarzan shouts out in triumph, along with Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., the foundation E.R.B. left behind.

By all accounts, Burroughs was a business genius far ahead of his time. He was the first American author to form his own corporation and protect not just his written words but also all subsidiary rights, including the yell. Imagine if the J.M. Barrie family had kept all subsidiary rights to everything connected to Peter Pan. Tinker Bell lunch boxes alone would have made them millions!

That shrewd business sense also extended to managing his personal estate. He saw that the city of Los Angeles had completely surrounded his Tarzana Ranch. He knew that lots would sell fast. So in 1923, Edgar decided to subdivide.

How much did the first lots go for? In 1923, you could buy a lot on what’s now the corner of Reseda and Ventura boulevards for $850. Burroughs left no stone unturned, even giving lot buyers instructions for planting fig trees and berries.

Within a matter of years, a local post office was established, and residents decided to hold a contest to choose a name for the community. With such a famous author as a resident, residents decided on the name Tarzana. The writer was, by now, an international figure, who packed much weight within the community.

Interesting to note: He was never mayor of Tarzana. He wisely kept his focus on publishing books and managing his expanding financial empire. He had to deal with the films. And the comic books. And the radio shows. And the TV shows. But most importantly, the films.

The legacy of Tarzan, vivid on celluloid, remains strong even today. Tarzan is the most filmed fictional character in motion picture history, with 41 feature length films. By comparison, the young upstart James Bond, who kicked off his first film in 1962, has just 23. And the first Tarzan film was also the very first movie to gross more than $1 million.

Speaking of being shrewd: In 1927, Burroughs made sure his son-in-law, James Pierce, was cast as Tarzan, while his daughter, Joan Burroughs, played Jane. (The couple later divorced.)

As the movie industry changed from silent to talking films, so did the character of Tarzan. And Burroughs didn’t like it. He quickly became disillusioned with the portrayal of the talking Tarzan.

He felt his character was made out to be a mono-syllabic brute barely able to speak. After all, his Tarzan first spoke French, then learned English before he ever met Jane, and eventually sat in the House of Lords.

Instead, it was the community of Tarzana that pleased him during that period, and he took great pride in its name. He enjoyed watching it take on a true air of sophistication and slowly fill with successful businesses and lovely modern homes designed by great architects like Gregory Ain, Richard Neutra and Marco Brambilla.

Edgar Rice Burroughs didn’t just write fiction; he also became an important war correspondent. He happened to be in Hawaii while the Pearl Harbor attack occurred. He was playing tennis and actually observed the Japanese planes dropping their bombs on the Pacific fleet.

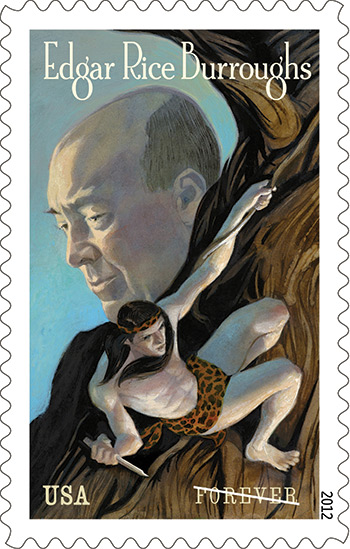

The USPS stamp released this past summer

in honor of Tarzan’s 100th birthday.

In his late ‘60s, he became the oldest war correspondent to serve in the Pacific theatre, flying from island to island reporting on troop activities …even going out on bombing runs with the U.S. 7th Air Force. He wrote about that too, with a total of 25 articles published about the fighting in the Pacific.

After the war, Edgar moved back—not to Tarzana but to Encino. Largely confined to a wheelchair, his large and rambling former home was too much for him to deal with, and he moved into a small home close by. But he still frequented his office building on Ventura Boulevard and continued to write from there.

His grandson John Burroughs, Jr. remembers playing in the front yard while granddad cranked out his fiction inside. By then, Edgar Rice Burroughs was famous enough that he was often referred to by his initials: E.R.B. However, with his family, he liked to call himself “O.B.,” which he said stood for “Old Burroughs.” John recalls, “Once he whispered to me ‘O.B. really stands for Old Bastard.’”

John tells a funny story about seeing “Old Bastard” put in a letter. He was sitting on his dad’s lap when a publisher called to tell his father they couldn’t pay the agreed-upon amount for his cover illustration of one of the Tarzan books. (John Burroughs, Sr. illustrated several Tarzan books). John hung up in a huff and told his father, E.R.B., about it.

Edgar Rice Burroughs in his military uniform with grandchildren (left to right) James Pierce, John Burroughs, Jr. and Danton Burroughs, circa 1942.

As grandson John, Jr. tells the story: “E.R.B immediately said ‘Write him a letter right now saying that if he doesn’t pay you the agreed upon amount, the Old Bastard who writes the books will never let him publish another!’” John, Sr. got paid in full, and the morning the check arrived, according to his grandson, E.R.B announced it was time for an “O.B. five o’clock cocktail to celebrate.”

Edgar Rice Burroughs died of a heart attack on March 19, 1950, having written almost 70 novels. He was cremated and his ashes buried under his favorite tree in the front yard of his Tarzana office building, where Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. is still located.

His grave is so close to the Boulevard, in fact, that grandson John remembers “hiding behind that very tree and throwing walnuts at the passing cars.” Edgar’s mother’s ashes are also buried there. Both graves are unmarked; apparently E.R.B. wanted to avoid attracting gawkers and vandals.

Today Burroughs, Inc. oversees every adaptation of the literary works in publishing, film, television, stage productions and all licensing and merchandising. The company also has licensing agents around the world who go to events where there is interest in the creations of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Just this past fall, an E.R.B. postage stamp was unveiled by the U.S. Postal Service at … where else? The Tarzana Post Office.